Can you improve on your weaknesses?

Endurance came easy for CW’s Michelle Arthurs-Brennan, but could she train her body to improve on her weakest area - sprinting?

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Let's be under no illusions: the physiological glass ceiling exists — your body’s limitations, though invisible, are real. World-class athletes need to know exactly where their limits lie: the areas where they have already reached their potential, as well as the areas where they can still reach for the sky.

But does the same apply to Joe or Joanna Bloggs — that is, you and me — who have no claim to world-class talent? How do we know whether the type of rider we think we are, with all our perceived strengths and weaknesses, accurately reflects our true limits?

I discovered bike racing via triathlon and then time trials. Riding on the red line for about an hour, holding a constant effort and tolerating the slowly rising level of discomfort, came naturally to me. My time trial heart rate trace was always textbook; I’d push up to a pain rating of ‘considerable’ and hit ‘extreme’ just in time for the flag.

But like most riders, I reached a plateau — and then started to get a bit bored. It was a problem easily solved by taking up track, crits and road racing. In those disciplines, you need to have a sprint, otherwise it’s a fast track to frustration. Judging by the way the peloton always seemed to power away from me in the final 200 metres while I fumbled for gears trying to hang on, the odds were stacked against me.

Is it even possible to retune your engine?

After two years of training at Herne Hill Velodrome, racing crits and road races, things had improved. As a side note, competing in bunch racing and forgoing regular time trial attempts had a positive effect on my actual time trial ability, resulting in a new PB of 56.03 last year – perhaps largely due to the new challenges presented.

Despite a handful of second places at local crits in 2017, I still felt I still had a long way to go in the pursuit of the elusive win – especially as I embarked upon the winter track league at Lee Valley.

So I enlisted the assistance of several coaches, a strength-and-conditioning expert, and my local Holland and Barrett, with one goal: undo the hardwiring that was restricting me to long, sustained efforts — to transform myself from a pure endurance rider into someone who could maybe even win a sprint.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Transformation works both ways, of course: there are sprinters looking to improve their ability to hold a high threshold for longer durations — and that’s shift I also wanted to investigate.

Physiology and training experience cannot be ignored, but the experts I spoke to agreed that most amateurs are able to change or adapt their specialism.

“As an absolute, a tiger won’t change its stripes. Sprinters are born, not made,” says Neal Henderson of Apex Coaching, who has coached Rohan Dennis and Evelyn Stevens to Hour record success and also writes the training sessions for The Sufferfest.

“Your innate strengths are what they are, though training can influence them to a degree. We can always have some impact on other factors of fitness and endurance dependent upon our training.”

Henderson explains that training age – the amount of time you’ve been training a certain discipline – is pivotal to the gains you can expect to make and how quickly you might make them.

“For an individual who has had very little previous sprint and peak neuromuscular-specific power training, it’s possible to see very significant changes in five-second power within just a few weeks of specific training. I wouldn’t be shocked to see a 10-20 per cent difference in five-second power after just a few focused weeks.”

“If an individual has training for a long time to improve their FTP power, then even an eight-week focused training block on FTP might yield only a two to four per cent improvement in FTP. In essence, the responsiveness does depend on your training history.”

When comparing the physiology of a sprinter to that of an endurance rider, it’s easy to get drawn into a discussion of muscle fibre types, fast- and slow-twitch. Henderson dispels this dichotomy by pointing out that we all have both types, fast and slow, and that not many people massively favour one or the other.

“Everyone has a different distribution of fast-twitch and slow-twitch muscle fibres. That said, it’s a bell-shaped curve, in that most people are about 50/50 fast to slow.”

There are of course anomalies, as Henderson acknowledges.

“At the end of the spectrum, a true sprinter — a woman producing over 1,600W or man over 2,200W — would have a distribution of around 80:20 fast to slow-twitch. An ultra-endurance specialist — think solo RAAM rider — is closer to 20:80 fast to slow. But even a 60:40 distribution is unusual, and 70:30 is toward the extreme.”

The key question is, can you convert slow-twitch fibres to fast, and vice versa?

“No,” says Henderson. “There is no evidence of change in muscle fibre type from fast to slow, and especially not from slow to fast.”

Some explosive fibres can be trained to be more resistant to fatigue, Henderson adds — for example, a sprinter may be able to work on their anaerobic capacity to improve their one-minute capacity. But you can’t convert or ‘grow’ new fast-twitch fibres.

Seven year switch

I have seven years’ training in my legs — most of it FTP-focused — but I’ve been riding track for the last two years. Though I can’t claim to be a sprint virgin, I've never focused on it specifically in a block of training. I began my experiment with two tests: an indoor FTP test, and an outdoor five-second max power effort, completed under instruction from a coach.

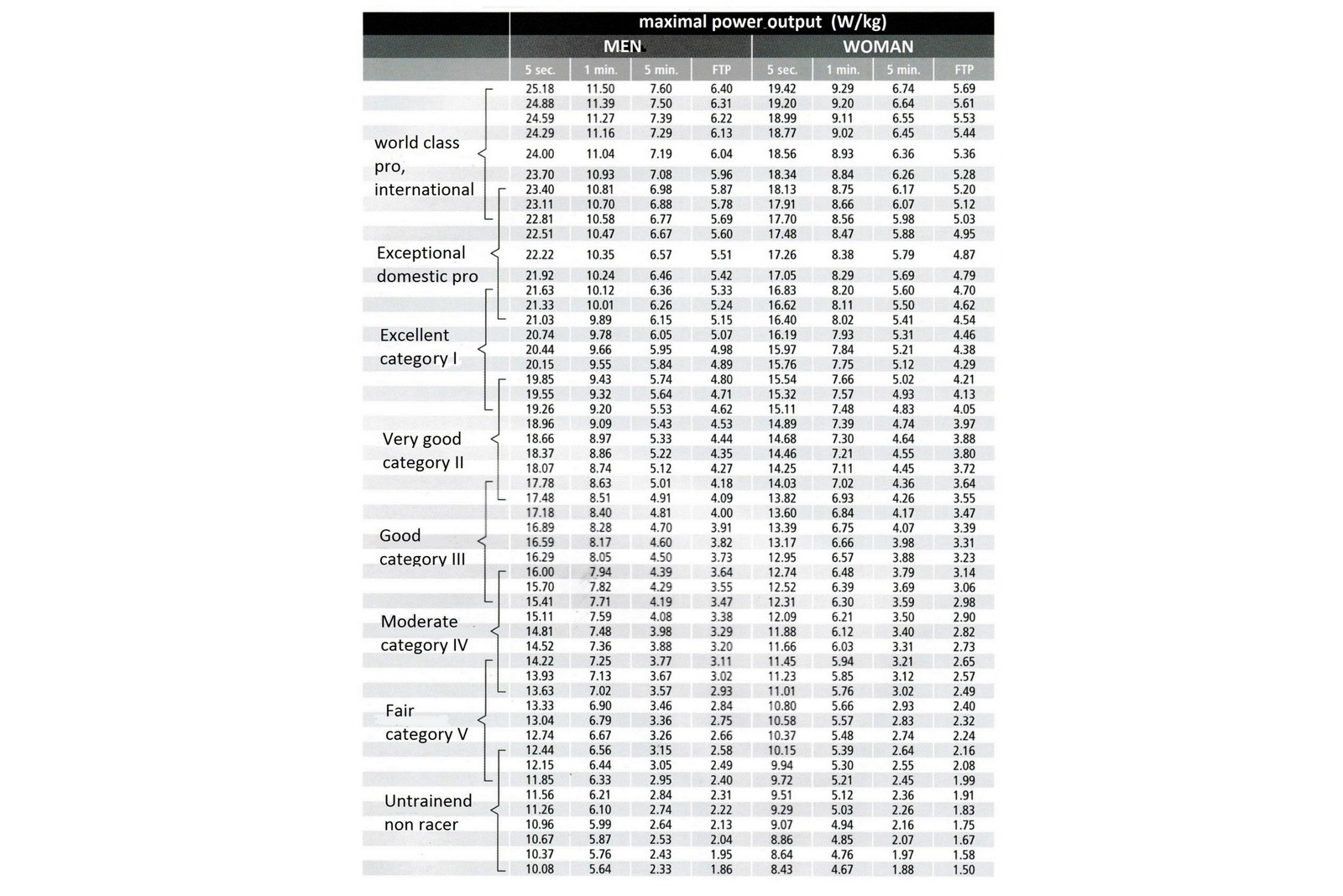

To establish FTP, I used the protocol as described in Training and Racing with a Power Meter by Hunter Allen and Anthony Coggan. My results put me at 3.9w/kg for FTP (219 watts), 4.3w/kg (251 watts) for five minutes and 10.9w/kg (636 watts) for five-second power. This situated me as ‘Very Good’ for FTP and in the middle of ‘Good’ for five minutes according to Allen/Coggan’s power profile chart. As for five-second power, I’m rated merely ‘Fair’.

There's some useful data on the differences between men's and women's power data here (though the sample size isn't clear) - but the chart still rates me against my own gender. If you could draw my five-second and FTP powers on a piece of paper, it'd look a bit like a seesaw with only one inhabitant who happened to exceed the equipment's weight limit.

I can’t say I was surprised by the results, but I had hoped that a couple of years of road racing might have boosted my sprint a little further away from the realms of “Untrained athlete”. Though I’ve continually insisted, “I’m not a sprinter”, 636 watts did sound far, far below the level I’d hoped for as my five-second output.

The training

To plan my training, I spoke to coach Jimmy George at VO2 Cycling in Kent. George began his career as a junior time triallist and later raced professionally on the road in Belgium, before retiring and returning to endurance in the form of triathlon. He was encouraging about my mission:

“I do believe you can change your rider type, because I’ve done it. But you need a goal, you need to plan it and monitor it. You can change — how good you’ll be… [is questionable].”

George drew attention to how much new regime would introduce very different types of training stimuli: “Now we’re going into power, speed, and acceleration, all that sort of work. I would be looking to have two key sessions a week — one to develop max speed, and one to develop acceleration.

Session one, focused on max power, involved performing four to six 20-second sprints, with five-minute recoveries. Session two comprised of sprints between five and twenty seconds, repeated in blocks of five with minimal recovery.

>>> How to train like a sprinter

George also had me drop Sunday club runs in exchange for steady 90-minute to two-hour rides: “You just don’t need to be doing the miles,” he said. Those aiming to improve their FTP would be focusing on ‘bread and butter’ sessions such as two times 20 minutes, and other intervals of between eight and 40 minutes.

Regardless of the goal – one thing is for certain: “Training has to be progressive. So you either need to add intervals, reduce recovery or look to put out higher numbers. In your case, work on hitting a new, higher target each week,” George said.

Undergoing this experiment, I was on a journey into the unknown — and in the interest of honesty, I met with George at the midway point. Up until week five, I’d already been doing the sessions he suggested but in a less organised, more scattergun way. The V02 Cycling coach really hammered home the importance of progression, and following his advice made the training considerably more productive. Every session suddenly became a target, a test, and the age-old idea that “every training session must have a purpose” took on a new meaning, which was both exhilarating and exhausting.

I felt more purposeful in training than I have in years. However, this came with pressure. It being winter, I managed to catch two colds during the process, which felt much more limiting than they might have in a normal training cycle. I was desperate to get back to full health so as not to leave a dent in the programme.

Training time — typically only an hour a day during the working week — also ceased to be the allotted time in which I could switch off my brain. Completing sessions with clear-cut targets was mentally tougher than just going through the motions as I have in the past.

Catching up after the experiment, George gave me some insight into how to maintain my gains (spoiler alert: there are going to be gains) without neglecting other areas — FTP, VO2 and so on — forever.

“You’ve done a big block of [sprinting]; you’ve now just got to keep it in your programme… and just keep revisiting it, reminding your body what it is you have taught it.”

He also reassured me that the gains will be long-lasting, provided I maintain them.

“[The gains] won’t go — you won’t revert back to square one. Now, your training age for sprinting is effectively 10 weeks. But if you keep training and training, your rate of de-conditioning will become slower — like your endurance now.”

Hitting the gym

Everyone knows that track cyclists spend a substantial amount of time in the gym, so I figured it was something I should consider. Pumping iron isn’t just for sprinters. I booked in at Surrey Strength and Performance in Carerham, which is run by GB coach Daniel Iaciofano.

“The benefits of strength training are numerous,” says Iaciofano. “You increase the ability to produce force, which is really good for sprint finishes and climbing — anywhere you need a burst of energy.”

The gains are not merely in power, Iaciofano continues: “Endurance athletes would benefit more from a postural point of view. If you increase rigidity through the torso, and the endurance of the postural muscles — torso and arms — they’re going to waste less energy over a 100-mile ride and pick up less overuse injuries, thanks to increased tendon strength and greater bone density, which means more time on the bike.”

Cyclists often favour high reps with low weight, under the belief that lifting heavy weights will result in bulking up and weight gain. According to Iaciofano, this is misguided.

“Body builders typically do higher reps, often trying to increase the cell size in the muscle — as opposed to their firing rate. When you do heavier weights, you get a benefit in rate of force development — the rate at which muscles are recruited.”

For cyclists, heavier weights and fewer reps are the order of the day.

“It’s not about repeating tons of reps because you’ll pedal lots on the bike – the two aren’t even comparable. What you’re trying to do [in the gym] is increase someone’s ceiling of strength.”

Iaciofona recommends doing four to six reps per set.

“When you do eight to 12 reps, you’ll get a ‘pump’ [hyperaemic swelling] — and that causes more DOMS. Cyclists doing one or two sessions [of low-rep sets] a week don't need to worry about weight gain, as long as calorie consumption is not at a surplus."

Deciding on the right exercises for you depends upon your strengths, weaknesses and flexibility — but there are themes.

“You want a couple of bilateral knee and hip dominant exercises: squats, deadlifts, Romanian deadlifts, hip thrusts. Then unilateral stuff: single-leg exercises such as step-ups, single-leg hip thrusts, single-leg Romanian deadlifts.”

And what about upper-body work?

“Although there’s no direct transfer of upper body work [to cycling performance], it’s good for health and you might get some core efficiency benefit, so stuff like press-ups, pull-ups, rows [are worthwhile].”

It's a common misconception that come race season, cyclists should drop the weights. Instead, Iaciofona recommends low volume sessions with heavy weights - that way you keep the stimulus, without that DOMS causing 'pump' the body builders seek.

"Off season, [you should aim to do] ideally two sessions a week – one would be an absolute minimum depending upon rider’s schedule. Provided good level of strength has been built up in off season, come race season one session every 7-10 days would be enough to maintain the strength built up in off season. DOMS normally come from a new stimulus, a lift you’ve not done before, or an increase in volume – so as long as you build up preparedness in the off season, when you drop it in the in season, you shouldn’t be getting soreness unless you're in a calorie deficit."

>>> Bulletproof your body: one hour per week to stay injury free

If you’re looking to add some strength work to your programme, a strength-and-conditioning coach can provide a lot of bang for your buck. Every strength session I did over the course of my programme was coached at SSP, and resulted in greater confidence, no injuries and limited the number of days walking like John Wayne.

Time spent in the gym has become a highlight of my training week. When picking up something new, it’s easy to see quick gains, and moving on to heavier weights each week has been challenging but confidence-inspiring — more so than my usual bike training. It’s true that there were DOMS, but generally they only lasted a day.

Raiding Holland and Barrett

There’s a number of supplements often recommended for cyclists, and when it comes to short-burst power, top of the list are beta-alanine and creatine. These are entirely legal for racers, available in regular food - though you’d have to eat a lot of meat - and recommended by British Cycling. Author of The Complete Guide to Sports Nutrition, Anita Bean, explained the benefits to me:

“Beta-alanine supplementation may be beneficial for efforts involving repeated sprints or surges of power. This makes it potentially useful not only for sprinters and track cyclists but also for road cyclists.”

Beta-alanine has a funny habit of giving you the tingles when taken in one go, so it is recommended that you split a total of four grams into evenly spaced doses of one gram. Not doing so isn’t dangerous, and frankly knocking back one gram of white powder four times a day is a bit of a chore, so I accepted the tingle.

Creatine, found naturally in meat, is a more track-specific supplement: “Creatine supplements increase muscle levels of phosphocreatine, an energy-rich compound made from creatine and phosphorus,” says Bean. “This fuels muscles during high-intensity exercise such as sprinting or lifting weights. The greatest improvements are found in high power output efforts repeated for a number of bouts.”

The oft-quoted side effect of creatine is weight gain, as Bean explains: “due partly to extra water in the muscle cells and partly to increased muscle tissue.” For this reason, road cyclists tend to avoid it. However, on a dosage of four grams a day, I didn’t notice any weight gain, which tends to happen only at higher dosages.

The results

Following 10 weeks of once-a-week strength training, twice-a-week sprint sessions and (mostly) daily creatine and beta-alanine, I gained an extra 10.69 per cent on my five-second power. After 15 weeks, I had upped that to a 16.67 per cent increase, hitting 742 watts — OK, I’m still not beating any records but I’m up to ‘Good’ on the Allen/Coggen chart. My FTP remained uncannily identical (219 watts) and I hadn’t gained any weight.

After this, I returned to more mixed training, and five weeks later I re-tested, using ‘Full Frontal’, the four-dimensional power test by The Sufferfest. In hindsight, I'd have used 'Full Frontal' for my opening test, too as it allows you to get a snapshot of your ability range all in one go.

My sprint remained similar at 717 watts (indoors), five minutes had increased from 251 to to 263 watts (4.5w/kg) and FTP was very slightly up at 223 watts; I hadn't gained any weight.

| Row 0 - Cell 0 | Week Zero | Week 20 |

| Five second power | 636 | 742 |

| Five minute power | 251 | 263 |

| FTP | 219 | 223 |

To be clear: I will quite obviously never be 'a sprinter'. But I've improved and I now feel more confident in my ability to attack during track races and, most importantly, no longer think of myself as the underdog in sprint situations.

In terms of results, I finished third overall in the Lee Valley Full Gas Track League, took second in the bunch sprint at the end of this season’s first road race, and finally won a crit race.

Overall, it's been a success and the experiment has led me to question how hardwired my FTP ‘specialism’ really was. Sure, long efforts do come more naturally to me than short-burst power, but it took years of grinding out long intervals to become ‘very good’ — whereas it’s taken just one block to reach ‘good’ at the short efforts.

Above all else, the initial 10-week period has driven home the importance of making sure training is always progressive. Early in a rider’s training life, every improvement is a stepping stone to greater improvement. But in time, we slip into a routine of 2x20 Tuesday, Track Session Wednesday and VO2 Thursday — drifting along, repeating the same sessions, without any real attention to actual progress or results.

Focusing on just one element allowed me to direct all my energies into it and achieve the result I wanted. That’s the key lesson here: you can (almost certainly) significantly improve an area you regarded as a weakness, but it takes a very conscious effort, and a progressive plan.

Hardwired or only in your head?

Are your strengths and weaknesses real physical phenomena, or ingrained beliefs that can be overcome?

Katie Page was a rower going for GB trials when a virus left her paralysed. She was told she’d never walk again, but proved the doctors wrong — a feat she believes was achieved just as much through positive psychology as through physical toughness.

When it comes to dictating our strengths and weaknesses, Page believes the mind plays a very important role.

“When you think of your strengths and weaknesses, you’re creating a belief. The more you tell yourself a belief, the more it can become truth — and this can be used to your advantage or disadvantage. You have to be careful with the thoughts you choose. We do choose our thoughts, and we can control our thoughts.”

This certainly resonated with me. I’ve lost count of the number of races I’ve openly prefixed with the statement, “I’m a tester, really — I’m not going to do well here.”

Adjusting thought patterns takes practice — and the author of 10 Secrets to Sporting Success has some practical tips. Firstly, focus on micro-milestones: “It’s important to be positive but realistic. Sometimes people’s expectations are very high, small improvements can be happening but they don’t see them. Rather than focusing on the big, ‘outcome’ goal, set up two ‘process’ goals based on things you can control.”

Secondly, learn what gives you confidence: “I do an exercise called ‘examining your peak performance state’. I have an athlete list their good performances, and some not so good. They analyse what they thought, felt and did before, during and after the event. You can see how much of your performance you can control. Take those lessons and create routines that work.”

Finally, document your progress. “It’s vital to take greater accountability of building on your strengths, and continually improving. After every session, ask yourself: What did I do well? What would I do differently? And, what gave me confidence?”

Dani Rowe on switching from sprinting to endurance

Dani Rowe, nee King, knows a lot about swapping disciplines. The former track Olympic champion switched from track to road in 2015

“I wasn’t quite world-class at sprint cycling. I could see other girls within British Cycling who were a step ahead and I didn’t want to just make up the numbers, so I thought about giving endurance cycling a go,” says Rowe.

The biggest change was in volume — more miles — which led to progress that Rowe found powerfully motivating.

“Every month I would be setting new PBs, and it didn’t take me very long, under the guidance of Rowe & King, head coach Courtney Rowe, to break into the British Cycling women’s endurance squad.”

Not downplaying the mental side of the swap, Rowe recognises her own resilience: "Cycling is a huge mental game. In road racing, at any point in a 160km race you could simply give in… I have never, ever given up — the limiting factor for me has always been physiologically. I think my mental strength is my biggest strength when it comes to trying hard.”

What would she advise others who are considering changing their riding specialism?

“Get some good advice from a coach. The transition is drastic, and the demands on your mind and body will be significant, so don’t waste your time and effort pedalling in the wrong direction.”

Rowe’s coach, her father-in-law Courtey Rowe of Rowe&King coaching, adds: "Dani has that race-winning power and speed as part of her DNA, which is what often wins bike races, [so her track history] is an advantage.”

That's not to say it was all plain sailing: “The change in training was pretty radical — but in a structured manner. As a full-time bike rider, we were able to throw Dani in at the deep end, as she had plenty of time to recover and few outside of cycling distractions. However, for a rider with big commitments like work and a family, the transition in training would need much more careful management.”

For amateurs looking to make a similar journey, Dani Rowe’s advice is: “establish some realistic goals and milestones to help with motivation, as you will likely be taking a step back in performance as you switch disciplines.”

Michelle Arthurs-Brennan the Editor of Cycling Weekly website. An NCTJ qualified traditional journalist by trade, Michelle began her career working for local newspapers. She's worked within the cycling industry since 2012, and joined the Cycling Weekly team in 2017, having previously been Editor at Total Women's Cycling. Prior to welcoming her first daughter in 2022, Michelle raced on the road, track, and in time trials, and still rides as much as she can - albeit a fair proportion indoors, for now.

Michelle is on maternity leave from April 2025 until spring 2026.