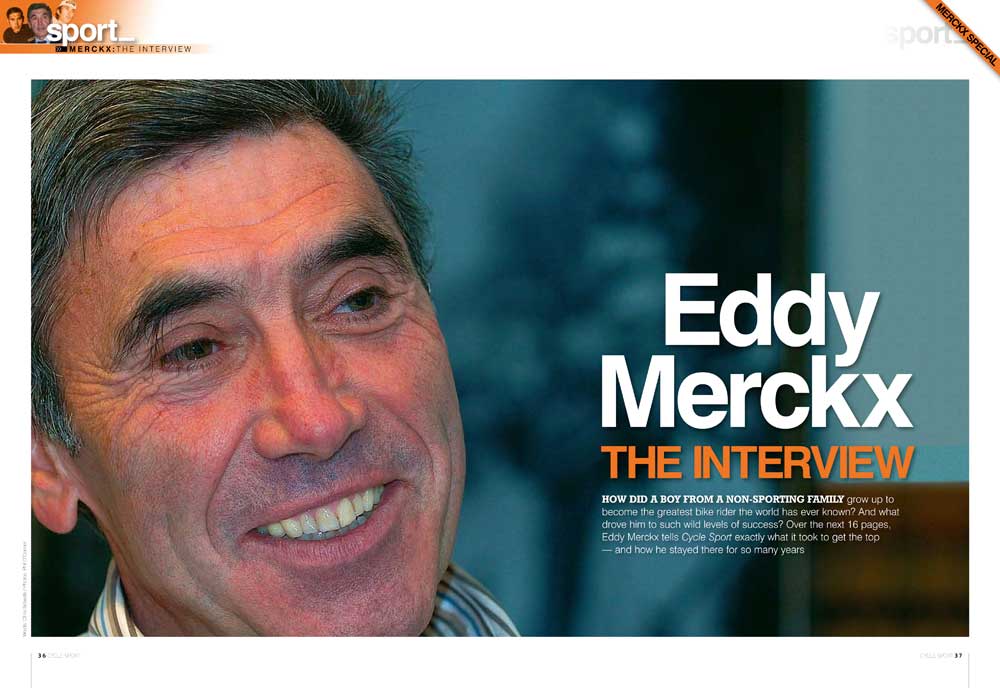

Eddy Merckx interview

We take a look back through the Cycle Sport archives for an interview with Merckx from 2004

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Cycle Sport visited Eddy Merckx back in 2004 as they put together a special issue dedicated to the greatest cyclist of all time. Now, on his 65th birthday, we take a look back at what the great man had to say.

Sat backlit and alone in the out-of-hours gloom of the Bradford Hilton Hotel's restaurant, Eddy Merckx wore the sphinx-like inscrutable expression that was his trademark during his racing career.

It was the same expression that has daunted many an interviewer before me, the same expression he wore when he was riding his bike at his best; blank, oblivious to what is going on around him, ‘in the zone' as they say in sport today.

Thankfully it is a mask, just the default setting for his features, the one that he uses when he's alone with the bit of Eddy Merckx that he has to keep back for himself, and as I was to find out, when he raced he truly was being himself.

As soon as I stepped into the room, proffered a hand and got the introductions out of the way, his face broke into a broad smile. Eddy Merckx public property was back. Attentive, searching for answers that would help me, with plenty of contact from his deep, brown, honest eyes.

Many bike riders when they're talking let their eyes wander. Looking upwards while thinking of an answer to a question, searching, trying to recall a feeling or sensation. Then when they speak, they look into the distance, off down some imaginary road perhaps, remembering being there. Not Merckx, he looks straight at you, weighing you up. It's a bit unnerving, but it gives him a real presence, and makes the interview much more intimate.

Bradford is a funny place to be meeting the greatest racing cyclist the world has ever seen, but our efforts to get some exclusive time with Eddy Merckx had coincided with those of the Dave Rayner Memorial Fund, a foundation that supports young British cyclists racing in Europe, to get a guest of honour for their 10th anniversary dinner.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

On a personal level it was also a privilege to spend some time alone with the man who, in terms of victories at least, has been further than anybody else in the sport. But the problem with interviewing a unique cycling icon like Merckx is, where do you start?

The beginning is always the safest place, so we open by talking about his childhood. "I had a beautiful childhood. I had loving, very sensible parents. We weren't rich, but my younger brother and sister, who are twins, and myself never wanted for anything. My father was a man of great character and my mother very warm and kind. Both of them were wonderful examples to me," he says.

Eddy Merckx magic moment - 1974 world championships

Merckx's heritage

We are all the product of our parents, so what traits did Eddy Merckx inherit from his mother and father? "Like everyone, I am a mixture of both of them. My determination and willingness to work hard came from my father. He worked tirelessly to build up his grocery business in the Brussels suburb of Woluwe St Pierre, where we moved to when I was very young. He was strict on discipline, but he was also a bit of a philosopher. I have kept some of his sayings in my head for the whole of my life.

"From my mother I get my softer side. An example of that is the fact that I often find it difficult to say no to people. They maybe don't mean to, but people can use you up if you let them," he explains, a little sadly.

While he was talking about his childhood, Merckx smiles a lot. He also has a hearty and rather sudden, sometimes surprising laugh. He can be talking seriously, frowning deeply, then he sees the humour in something and bursts into laughter. It is a good stress reliever.

No one in the Merckx or Pittomvils - which was his mother's maiden name - families was a cyclist or into any other kind of sport, but legend has it that Eddy Merckx got his first bike at the age of three and from that moment it was difficult to separate him from it. "Yes, I raced everywhere. The locals nicknamed me ‘Tour de France'. I was an outdoor kid anyway, always exploring, always in trouble. But the bike gave me more freedom, it widened my horizons," he says.

He got his first racing bike, a second-hand one, at the age of eight and admits that already he wanted to race at that age. But why? No one in the family was an example to follow. Neither did any of his neighbours race, because Woluwe was a middle-class suburb, and in 1950s Belgium, cycling was definitely seen as a working-class sport. Why, then, did an eight year old from that kind of background want to do something so alien to him?

"Who knows," he says, looking skywards. "It was a calling, a vocation perhaps. Something that was just meant to be."

It is an interesting thought, though, the genetic blueprint that created the physical wherewithal for such a great champion somehow getting the message through to his brain. How does science explain that? Merckx tries: "I got enormous pleasure simply from riding a bike. So I guess racing was a reason for riding it more. Later I raced a lot because it was my métier. It was where I felt confident, where I was Eddy Merckx. I loved to race. In races it was just me, the bike and the race. It was a joy, even after my crash in Blois [see separate box] and cycling was harder for me, painful sometimes; it was still a joy. In a race I had no controversies to confront, no organisers, no journalists asking questions. I could just express myself."

The young Merckx started racing at 12, with little success at first. But like other boys of a similar age he found a hero. His was Belgium's Stan Ockers, a world champion who, in a twist of fate considering Merckx's near-death experience in Blois, was killed in an accident while racing on the Antwerp track in 1956. Why did Merckx pick out Ockers?

"Because of the Tour de France. Ockers had won stages in it, won the green jersey twice, and he had finished second overall twice. He was always in the news during the Tour de France, and the Tour de France was everything to me. I didn't even know much about the Classics because they were held on a Sunday, and on that day we used to visit my grandmother at her farm in Meenzel-Kiezegem, where I was born."

Meenzel-Kiezegem is in the Flemish part of Brussels; Merckx grew up in a French-speaking part. His name is Flemish, but he is entirely bilingual. It can be a hot question to ask, but does he regard himself as a Flemish person or a French-speaking Walloon? "Neither, I am a Belgian," he replies quickly. I guess he's been asked that one before.

Merckx turned professional in 1965 for a Belgian team, Solo-Superia. Second place in the Belgian National Championships to Walter Godefroot brought him selection for the World Championships in San Sebastian, Spain. The winner that day was Britain's Tom Simpson. In 1966, unhappy with the attitude that his first team leader, Rik Van Looy, displayed towards him, Merckx transferred to the Simpson-led, French-based Peugeot-BP squad. Was that a happy move?

"Definitely," and here he laughs out loud again. "From Tom I first learned just how to celebrate after a victory. Tom loved to win and loved to celebrate. There is joy in victory, it is only natural to celebrate."

"The atmosphere at Peugeot was totally different. All I got from Van Looy and his cronies was ridicule, not one piece of help or advice. They were very unfair, I was still just a naive young boy really. With Peugeot, and especially with Tom, it was different."

What else did he learn from Simpson? "For a start I learned that he was a very good rider. He really put me in my place when he won the 1967 Paris-Nice, after I thought that I was on the way to winning it. But he also taught me a lot of technique. Tom was a very good technical rider, a good descender for example, good at placing himself in the peloton or in a sprint. He taught me patience, too. ‘Step-by-step Eddy,' he used to keep saying to me, ‘Take it step-by-step.' I was so anxious to improve. Most of all, though, he taught me bravery. Tom was a very brave man."

Eddy Merckx magic moment - 1975 Tour de France

Respect for a friend

Is that why he attended Simpson's funeral, held at Harworth in England? "Tom was a fallen colleague. I had to go. His death was such a shock. I was sitting at home, watching the television news and it just came on. You felt that you had to do something practical. But what? Going to the funeral was the only practical thing I could do."

Merckx agrees that he is not an academic. "I hated school, I loved doing all the sports, but I hated to be inside. I left as soon as I could. It caused friction at home, especially with my father. But it was typical of him that he supported my decision, especially when he saw that I loved the thing I had chosen, cycling, and was doing well at it," he says.

However, there is one subject he does know a great deal about, and that is art. "I love fine art, my favourite artist is René Magritte, he is a Belgian surrealist. I once owned a Miro, which was stolen. Salvador Dali is another favourite of mine. I find that kind of art fascinating and thought provoking."

By the end of 1967 Merckx was world champion, regularly winning Classics and shaping up for his emphatic victory in the 1969 Tour de France, the victory that he says he is most proud of, and in his mind still stands out above all his others. He was so gifted, winning looked easy. Merckx humbled the opposition. It was his golden period, the one that he can't help smiling about when speaking of it. But then at Blois it all changed.

Dreams come crashing down

"The crash in Blois was terrible for me. From that day cycling became suffering," he says. What exactly were the injuries he sustained that day? "A lot. I had stitches in my head and was scraped and bruised all over, but those injuries healed. I was lucky in a way in that I could have been killed, but the problem that crash gave me was the damage it did to my back," Merckx reveals

"What happened was that my hips were knocked out of line with my body. It meant that my legs were also out of line with the rest of my body. After that day I could never sit comfortably on my bike again. I tinkered with my position and changed my frame angles. I would keep many bikes, all subtly different, all ready to race on, but I never found comfort. Before Blois I cannot say that I suffered in a bike race, not even in the Tour de France. I just pressed on the pedals when I wanted to, that was all I had to do

"After the crash it was never the same. The pain changed from day to day, some days I would weep on my bike, on others it was OK. One time, towards the end of my career, it was so bad that I was riding up the Alsemberg hill in Brussels and I wondered if I was going to get to the top. I thought that I might have to get off and walk, and it isn't a very steep or a very long hill. My back became my weakness. It still affects me even today. I cannot jog to keep fit because of my back."

It seems incredible that Merckx won most of his races after such a debilitating injury. Would he have won more races if it hadn't happened? "No, not more, but I would have won with greater facility, greater élan. I would have won stage races, like I did the 1969 Tour, by many minutes instead of just a few."

The first moment of despair

The suffering became more apparent as time went by. The 1970 Tour looked like a fairly straightforward victory, but then came 1971 and a humbling at the hands of Luis Ocana. He was staring defeat in the face during the Tour de France until the Spaniard crashed. How did that feel?

"It was terrible, but a lesson. That year, that Tour, was a low point. After it I realised that I had to take my back problem seriously, and I brought in osteopaths and worked hard at exercises specifically to help improve my back. My back was robbing me of power, but in 1972 I took more control of it, I managed it better," he says.

That was the year that Merckx made a successful attack on the World Hour Record. Would he have gone further if he hadn't been hampered by his back injury, and would he have done more if he'd had extra time for specialised training, considering that his attempt was at the end of a season where he'd competed in 127 races and won 50 of them?

"But for the back injury, yes, I would have done many more metres. Regarding specialized training, I did all that I could. I consulted sports doctors, who had experience with sport at altitude, because I did my record in Mexico City. I trained on the home trainer with an oxygen mask, breathing the same mixture of air that I would find at altitude. I also used all of the best equipment that was available to me at the time.

"Speaking as a bike enthusiast I would have liked to have had a go on the equipment they used for the record in later years, though. Also, I would have gone further on a modern indoor track. In Mexico it was outdoors, where the wind is always a problem. You wait for the best conditions, but in the end you have to take what there is," he says.

Eddy Merckx has always said that he suffered a lot to break the Hour record. Was there any time during the attempt that he thought he would have to stop? "Not stop, I did suffer, particularly during the time between the 40th to 50th minute. After that the suffering was the same, but the minutes count down easier, so you can still hang on."

Does he think that the new Athlete's Hour record is a good idea; does taking out the element of equipment improvements create a more valid comparison? "Yes, it shows something, but the tracks are not the same, conditions cannot be the same, other things too. A record is a record on that day."

Earlier in the interview Merckx had spoken of his inability to say no. Does he feel that he raced too much during his career, and could the amount of racing he did have shortened his career? "No I don‘t think the amount of racing I did shortened it, but the fact that I continued in the 1975 Tour de France after I crashed definitely did shorten it."

Carrying on too far

"My build-up to that race had already been problematical, and actually I wasn't in the best of health when I started it. But after the crash, in which I fractured my cheekbone, I suffered like you cannot imagine possible. I could not take in anything but liquids. I had to race on empty."

Why did he continue? "I had to for the sake of the race, for honour and for my team-mates. They depended on my prize money. Remember that I still finished second," he says with pride. "What I should have done was pay my riders out of my own pocket and left the race. Then maybe with my strength rebuilt I could have been competitive in 1976."

Looking after his team-mates is important to Merckx. Patrick Sercu told us that it was Merckx who took on all the negotiations to set up his final team, even though his heart was no longer in bike racing. He did it so that his team-mates would get paid for another year. He also provided jobs for former team-mates in his bike factory, although he plays that down. "It was only three of them," he says modestly.

Nevertheless, his team was very important to him. He demanded loyalty, but as his actions in not quitting the 1975 Tour show, it was loyalty that he repaid. Which of Merckx's team-mates stand out in his mind?

"I cannot chose one. Joseph Bruyere, yes. Roger Swerts and Jos Huysmans too. They are obvious choices, because often they were with me towards the end of races, but there were others who had done their jobs long before. You didn't see them fetching bottles, stopping to help riders who had punctured. Their job was done before the finale, but it was just as important."

Valour and victory

His sentiments about his team-mates are indeed one of a loyal and honourable man. Loyalty and honour are words people use regularly when describing Eddy Merckx. If there has ever been any criticism of him, it has always been about the same thing, his desire to win every race in which he competed.

However, it is criticism that Merckx is totally at a loss to understand. "A race has to have a winner," he says, getting quite agitated. "The whole point of a race is to find a winner. How can you take part without trying to win? How can you be criticised for doing what is the object of your chosen work. I chose to race, so I chose to win. A doctor works to cure, surely a sportsman works to win, doesn't he?

"It's funny, but every great sportsman has that attitude and every great sportsman gets criticised for it. Michael Schumacher today is in the same position as I was. They say that he is killing his sport by simply doing what he is supposed to do, doing what sport is all about. I do not understand it." He shakes his head, but allows himself a wry smile - we mortals must appear a funny lot from where he is sitting.

Which of his competitors did Merckx have the most regard for? "Felice Gimondi, because he had most reason to resent me, but I never felt that he did. He is a little older than me and while I was developing as a rider, he had already won the Tour de France at his first attempt. Gimondi won the Giro d'Italia and Classics like Paris-Roubaix, too.

"Cycling was his until I came along, yet he was always the epitome of dignity in the way he conducted himself during the many battles we had. I admired his strength of character, his courtesy, too. He was very dedicated, ascetic almost. He raced like a gentleman and brought a great deal of credit to our profession," says Merckx.

What about his life today? Does Merckx enjoy the engagements he goes to, like the one in Bradford that he was attending that night? "Yes, I like to meet people. It isn't good to be alone too much, you can sink into the past and that is unhealthy. Sometimes I don't understand the interest in me, though, and it is a bit overwhelming. In Britain you have many great champions now, I would rather be applauding them," he says, looking genuinely mystified.

Internal inspiration

I always like to ask bike riders from another age when they would have preferred to have had their careers, now or during the period when they actually did ride? They all say that the money on offer in cycling today would have come in handy, and Merckx agrees with them on that. But most say that they'd have found the increased pressure to perform today a lot more difficult to deal with, and were glad that they raced when they did. Many also say that they feel that there was a greater sense of camaraderie between the riders in times gone by.

Not Merckx. He accepts the camaraderie, but says: "The biggest pressure to perform came from within me. No one could have put more pressure on me to win than I did myself. No one ever had to motivate me, except when I knew that it was finally all over at the beginning of 1978. Then nobody could motivate me, I had made up my mind to go."

Merckx simply ran out of steam in 1977. Two years before, he could have won his sixth Tour, but 1976 was spent counting the cost in terms of ill health for carrying on in the 1975 race. What did it feel like riding in 1977 compared to the sensations he'd had when racing before?

"It was no different until the season got into full swing. I prepared well and actually won my first big race, the Tour of the Mediterranean, but as soon as more racing came along my body failed. I kept catching colds and other minor illnesses, where before I rarely did. I started to get little niggling strains and injuries too.

"Still, I was sixth in the Tour de France that year, and won 17 races. Wouldn't Belgium like to have someone who could finish sixth in the Tour now?" he says, brightening up. "But deep down I knew it was gone. The difficulties I had setting up the team for 1978 were the final thing. I said when I stopped in the spring of 1978 that the barrel was empty, and it was."

What about cycling today, what does he think of the ProTour idea for example? "Broadly speaking, I think that it is a good idea. It should raise the profile around the world of races other than the Tour de France. The Tour has always been important. If you were to ask bike riders why they took up cycling in the first place, I bet that 90 per cent would say that it was because of the Tour de France," he says.

"But since the sport got more worldwide publicity, as people from more nations became involved, it is only the Tour de France that is being seen. The ProTour might change that and raise the profile of other races that we know so well in Europe but are not known elsewhere, like the Classics for instance."

Conceptual concerns

"But I do see that there may be two possible problems with the ProTour. The teams in it are going to have to do more races, so they will need to be bigger and have bigger budgets. The other problem is for very small races, or young races. Are they going to be able to continue? I am involved with the Tour of Qatar; we need eight teams for that race, so far we only have two that are definite for the 2005 edition," Merckx says.

While talking about modern cycling, the subject of Eddy's son Axel Merckx's cycling career cannot be ignored. "I have to say that I admire Axel for what he has done. It was brave of him to become a cyclist. He is like me and likes to let his legs do the talking, so I was very pleased about his Olympic bronze medal. He now has something of his own, something I haven't got," he says proudly, but then the flame of competition flares just a little.

"Of course when I did the road race in 1964 they only pulled me back in the last kilometre. And if I had gone to Mexico in 1968, who knows what I would have done? But the Olympics were for amateurs then, and I was a professional," he adds without a hint of a smile. He isn't being ironic either. Just in case anyone should doubt it, Eddy Merckx could have won an Olympic medal, and it obviously matters that we know it.

Back to Merckx's own career, which of his many talents - natural ability, dedication, drive or intelligence - does he feel was the one that made the difference, the one that put his record head and shoulders above, and probably out of reach, of any other professional bike rider?

"My natural ability. I had a very good engine, I produced a lot of power. I had speed, especially after a long race, I had stamina, but more important than all those things is that I had a terrific constitution. Many bike riders have the right natural abilities, but you need good health to exploit them. You need to be able to cope with constantly training, racing, travelling and constant changes of food, climate and weather conditions. Also there are the interviews, meeting sponsors and presentations. You must do all this and still keep healthy," he says.

Slowing down

"Until the final two years of my career I could do that. Even now I am busy, but my pace of life doesn't bother me too much, although recently I have had to be a little more careful, watching what I eat and watching my weight. But I am nearly 60 years old now, remember," Merckx points out.

Merckx can look tired. Some of it is probably because he's heard it all before at a thousand receptions, and during several thousand interviews. But then something, some subject, interests him and his face comes alive and his eyes sparkle. Frankly, although I knew it, I was taken aback when he said he was nearly 60.

He was very interested to know why we were doing this special issue of Cycle Sport, and especially interested in the riders we'd spoken to. I reeled off their names: Walter Godefroot, Patrick Sercu, Felice Gimondi, etc. To each one he listened solemnly and nodded his approval.

Then, knowing of their 30-year feud, I couldn't resist adding. "We've also spoken to your new friend, Freddy Maertens," I say. Merckx's face broke out into his sudden laugh. "Oh yes, Freddy. We were on the television together last week in Belgium you know, like that." He mimed putting his arm around an imaginary companion sitting next to him. "I am happy about it, though. It has been a long time between us two. Too long." He looked away again, the sphinx was back. Having a moment with his regrets, perhaps?

Interviewing a legend is always interesting, for the interviewer at least. Eddy Merckx hadn't displayed any lack of patience, and answered everything without seeming to hold back. I was happy, but I have to say that his best answer was given that night during a post-dinner interview in front of all the Dave Rayner Fund guests. It was to a question put to him by the evening's master of ceremonies, the former world pursuit champion Hugh Porter.

Hugh had gone over bits of Eddy's career and got to the defining moment of the 1969 Tour de France. It was where, at the top of the Tourmalet climb with 130 kilometres to go, Merckx, already in the yellow jersey, attacked and cleared off alone to win the stage by eight minutes.

"Why did you do that?" asks Porter. Merckx, the spotlight shining on his face, is lost for a moment. He searches his mind for some kind of logic that we will understand, something that we will be able to relate to. Different ideas flicker, but there isn't any logic to what he did that day.

Suddenly he realises it and his face collapses into childlike innocence, he shrugs his shoulders, smiles and says, "Because I'm crazy." It brings the house down.

Founded in 1891, Cycling Weekly and its team of expert journalists brings cyclists in-depth reviews, extensive coverage of both professional and domestic racing, as well as fitness advice and 'brew a cuppa and put your feet up' features. Cycling Weekly serves its audience across a range of platforms, from good old-fashioned print to online journalism, and video.