Corima wheels factory tour: is this the wheel brand with the most control over design?

Corima's journey has taken it from supplying tools to the carbon-fibre industry to manufacturing cutting edge bike wheels. With record breaking track bikes thrown in for good measure.

“Bikes are too inconvenient”, asserts Tommy Voeckler as we rode out from the Hôtel de l'Atelier, leaving the tiny tables spilling out into Marsanne's village square and winding our way over the climbs lining the Rhône valley, in Southern France.

“Jogging is better for travelling; you only need shoes and it takes less time.” Juggling brand ambassadorship roles may have forced a switch back to the sport he's best known for (Voeckler's here today on behalf of French wheel manufacturer Corima), but the latent talent residual in a multiple Tour de France stage winner and serial wearer of the maillot jaune isn’t something that just goes.

On the final hairpins up the Col du Pas de Lauzun, Voeckler stopped holding back and opened up a sprint to the top. There’s always a curiosity in how your own performance might stack up against that of a former pro, but I didn’t have a chance even to shift gears before he was already up the road. I guess that’s the most definitive answer I could have been given.

Enough of that, though. Let’s back up a bit to my tour round Corima’s wheel factory, looking at what it is, exactly, that the brand is doing out there – the setup it has is pretty unique.

The beginnings

Just outside the town of Loriol, in the flatlands down the middle of the Rhône valley, Corima's factory has been at this exact site for almost 50 years.

At the start, the brand's business had nothing to do with bikes. Instead, Corima was manufacturing the tools that other companies would then buy and use for producing carbon components themselves. The bulk of the business came from the aerospace industry.

In the early days, the smell of wood and sawdust would fill the workshop, I was told by Pierre-Jean Martin, Cormia’s Chief Technical and product Officer. Back then, metals weren't yet the ubiquitous materials they now are for the shaping of carbon parts.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

It wasn’t until 1988 that the company took the next step to actually producing carbon components itself, starting with full-section disc wheels and then branching out into track bikes within five years.

With complete control over every part of the process – the design, the manufacturing of the moulds, and then the production itself – Corima was able to iterate on its designs with particular speed.

The crowning glory from that time has got to be Chris Boardman’s breaking of the hour record, riding 52.270km in July of 1993. Astride Corima’s Cougar frame painted in the brand’s signature colour and rolling full carbon – and yellow accented – four-spoke wheels, it’s a build that sits in the pantheon of iconic bikes.

But that all came to a head around the turn of the millennium. Pierre-Jean Martin explained how Corima wanted to continue to innovate as it had been – as well as providing durable and serviceable products. But all that really adds to the costs.

Selling complete bikes, with the necessary buying of all the groupsets and finishing kits to go with them, was deemed to have bloated the company a little too far. Plus the UCI changed the rules on frame design, so Corima would have had to go back to the drawing board on all the designs.

Not that it was an easy decision, but at least it was clear, Corima chose to leave the frame building part of the business behind and focus instead wholly on its wheels. Given that’s where Corima started in 1988, when it expanded beyond manufacturing just the tools, it has a certain circularity that’s quite fitting for the brand.

The factory

It was a quick walk from Corima’s atrium – bedecked as it is in wheels, bikes and posters paying homage to victories and products, past and present – to the factory proper where the wheels are built by hand.

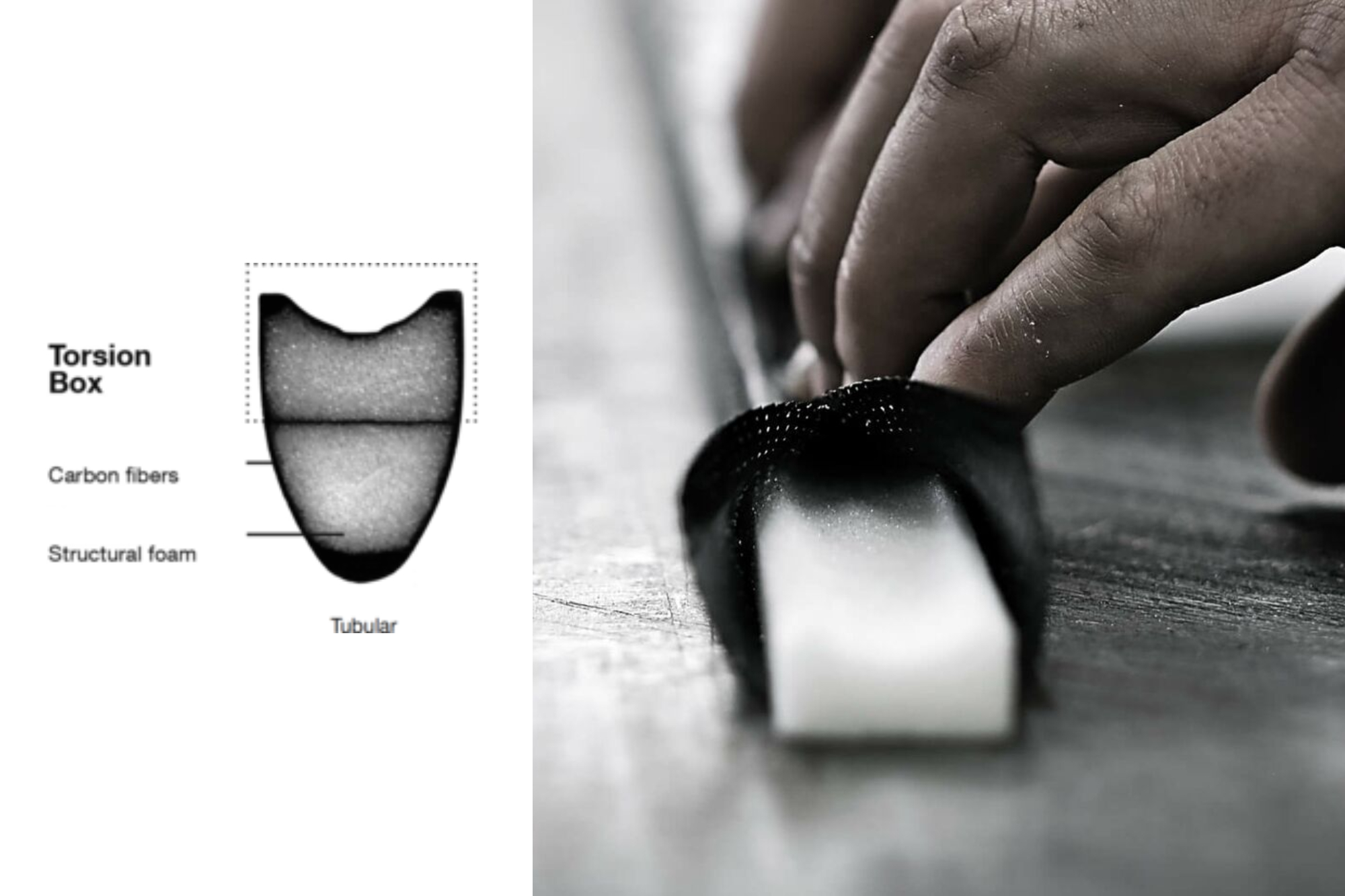

The first part of the process I saw was the laying of the carbon for the rims. Here, sheets of woven carbon are wrapped around solid steel wheels to provide their shape. The walls of the deep and shallow section of the wheels are left notably thin – too thin to offer the structural rigidity required just on their own.

Instead, Corima places a foam inside the internal section of the wheels to provide the necessary support. The reasoning being that the combination of foam and thinner carbon is supposed to work out as lighter than using a thicker carbon layup and relying on only that for the integrity of the structure.

The 32mm deep tubular MCC DX wheels are claimed to weigh in at 1,295 grams, which is very much at the feathery end for most wheel manufacturers – specialist brands such as Lightweight and its Meilensteins aside.

The clincher version is rather more modest, though, with a claimed weight of 1,495 grams, which some brands are able to hit with tubeless ready wheelset around the 50mm deep mark.

But weights aside, the rest of the construction of the MCC is just as notable. Each wheel uses a total of 12 carbon spokes which are rolled by hand from a single piece of unidirectional carbon fibre. The fat, almost pencil-like result is quite distinct from the thin carbon spokes that are almost mistakable for metal used on wheels from the likes of Hunt and Cadex.

To ensure the strength and quality of the product, these spokes get popped into a machine that places a load across their length – if the spoke deflects too far, it gets tossed aside and won’t be used in a wheel.

The hubs, also made mostly from carbon, are created on site by Corima, too. Building the wheel takes place on a metal jig with clamps all around the sides holding everything in place. it’s quite an art bonding the spokes together with the hub and rim to make for a wheel that’s perfectly true – and that’s the first test for the wheels once they’re let out of the jigs.

In manufacturing each part of the wheel – and in manufacturing the tools, jigs and moulds for the production of these parts – Corima is quite proud of the serviceability and customer service it can offer.

I was told that if you have any issue with the wheels, you can send them back to the factory where they'll be able to repair and replace any parts as necessary. With the MCC wheels, for instance, the spokes are bonded in place and shouldn’t ever need truing – but if you do manage to break a spoke, Corima will be able to simply set in a new one for you, fixing an otherwise unrideable wheel.

The testing

At the far end of the factory, I was taken to the area where all of Corima’s testing equipment is kept. There’s one which simply tests the impact strength of the rims, with weights crashing down directly on the carbon. There’s another which is for measuring the lateral stiffness of wheels, applying a force against the side of the rim.

Quite an interesting one was for measuring the inertia, with a wheel dangling off a string by the hub and slowly rotating back and forth. Then there was a huge steel drum for measuring the rolling resistance of the wheels when set up with different tyres.

It’s quite a common point that what’s fast on a smooth surface isn’t necessarily fast on coarse and pitted tarmac – the tyres and pressures used in the velodrome are quite different to that in road races.

I asked Thomas Dupont, Corima’s R&D Group Composite Manager, about this point and he was quick to tell me that this isn’t the only data they’re working off for the designs.

A significant proportion of Corima's time is now spent testing the wheels outdoors and in real-world conditions – although still controlling as many variables as it’s possible to. The bikes are bedecked in sensors, including those for measuring wind speed and calculating the coefficient of aerodynamic drag.

Thanks to the 12-year partnership with Team Astana, Corima’s been able to enlist the help of pro riders with the testing – particularly useful as they’re much better at replicating and maintaining their position on the bike than an average rider.

With Corima’s history in the velodrome, there’s naturally a heavy emphasis on the aerodynamic performance of the wheels, too. A large part of its design process is using modelling with Computational Fluid Dynamics software, but that’s supplemented with regular trips to the wind tunnel for more concrete validation of the designs.

The ride

We headed out from the village of Marsanne on a ride cruising across the flat plateau and taking in a variety of gently winding climbs and steeper kickers. Although the roads were mostly lined by empty fields, around the easternmost point of the route we dropped through the pas de lauzens, a valley with sheer craggy rock faces rising up on either side.

“When the skies are a little clearer, you can see Mount Ventoux from here,” Thomas Dupont tells me as we knock things back a little, spinning along the flat. “It’s a big day, but you can ride there and back again in about 200km – it’s not out of reach”.

But although it turned out to be bright and sunny on the day, I was told it’d be raining steadily through the weeks beforehand – with that unpredictability of the early spring weather, I was quite happy just pedalling around 50kms for this time.

As we climbed back up the hills, Tommy Voeckler, as Corima’s Brand Ambassador, lent over to tell me: “I really like the ride of Corima’s wheels. You can feel it’s much smoother than from other brands – can’t you?”

It was true. With what’s normally a carbon-walled echo chamber completely filled by Corima’s supporting foam, there was none of that hollow rattling and clattering you generally get from deeper section wheels. It was quite an improvement, but there are some other points about the wheels I’ll get onto later.

From the wheels, we got onto riding, with Voeckler confessing: “I don’t ride so much anymore, it isn’t so convenient as jogging. I can pack just a pair of trainers, some shorts and a T-shirt and get my training in straight from a hotel – and it takes just an hour or so.”

“I talked a lot with my coach and built up slowly, but now I’ve run a half marathon in 1hr 17mins – I’m happy with that.”

But given his sprint on the steepest slopes and up to the high point of the ride, it’s clear that despite the protestations, there’s still some training on two wheels being mixed in. When I asked about any plans for events this year, Voeckler elaborated: “I’ll be racing a 70.3 Ironman this summer, I’m feeling good about the bike and the run, but the swim a little less so. We’ll see how it goes.”

But back to the wheels. For the loop, I was riding the WS Black 47 wheels, a step down from the flagship MCC DX, these use conventional steel spokes and an aluminium hubshell – as such, a little less of the manufacturing for these is done in-house at Corima’s factory.

I’ll caveat my thoughts by pointing out that this was only a single ride I’ve put into the wheels and it was on a bike I haven’t ridden before – so my first impression is very much only skin deep.

But with that said, the wheels felt like they held their speed well on the flat and up those steady and winding five per cent inclines that don’t require a departure from the big ring. And, as Voeckler pointed out, the foam filled rims do an excellent job at sounding out any hollow rattlings from the road.

But when it comes to the spec sheet, things don’t look quite so good for the WS Black 47. The claimed weight is 1,720g, though, and cost around £1,360.00 / $2,200.00. To put that in perspective, we’ve weighed Zipp’s 303s wheels at 1,544g and those have a depth of 45mm and cost $1,300 / £985.

If you’re after lighter wheels, at a lower weight and a wider internal rim width (23mm vs 16mm), then the Zipps would be an obvious choice - and there are other brands more competitive than that still.

But whilst at this mid market price point, the gap for those key stats is evident, it does narrow (although not completely closing) at the highest tiers – and they are notable in their continuing French construction.

What's next?

First off, Corima has had a pretty good pandemic. Its supply chains are really quite short, buying the carbon from local suppliers. Whilst other brands have had to struggle with shipping delays and increased costs, Corima actually had a surplus due to the aerospace industry winding down its production and so reducing their normally high demands for carbon.

Although Corima is very much standing by its reputation for rigorous testing and detailed design – it's won Olympic gold medals with the Chinese track team and are very excited about supplying the French national team for the Paris 2024 games – certain aspects of the wheels are starting to look a little out of step with where other brands are heading.

Tubeless for example. Brands such as Zipp and Hunt have taken up the tech with both hands, but Corima still has a very strong focus on its tubular line. To an extent, this does make sense – tubulars are very popular among the pro peloton and there’s still a huge demand for the tech at the top level, even if much less so amongst amateurs.

But the brand has recently released tubeless-ready gravel wheel with a 22mm internal rim width and claimed weight of 1,560 grams, and I got from Thomas Dupont that they’ve got a some big projects in development, so stay tuned for those.

After winning the 2019 National Single-Speed Cross-Country Mountain Biking Championships and claiming the plushie unicorn (true story), Stefan swapped the flat-bars for drop-bars and has never looked back.

Since then, he’s earnt his 2ⁿᵈ cat racing licence in his first season racing as a third, completed the South Downs Double in under 20 hours and Everested in under 12.

But his favourite rides are multiday bikepacking trips, with all the huge amount of cycling tech and long days spent exploring new roads and trails - as well as histories and cultures. Most recently, he’s spent two weeks riding from Budapest into the mountains of Slovakia.

Height: 177cm

Weight: 67–69kg