In Pantani's shadow: The plight of Italian cycling

On one side of the door the light is golden and vibrant, the glow provided by Fausto Coppi, Gino Bartali, Felice Gimondi and so many other legends of Italian cycle sport, their exploits captured in grainy black and white images.

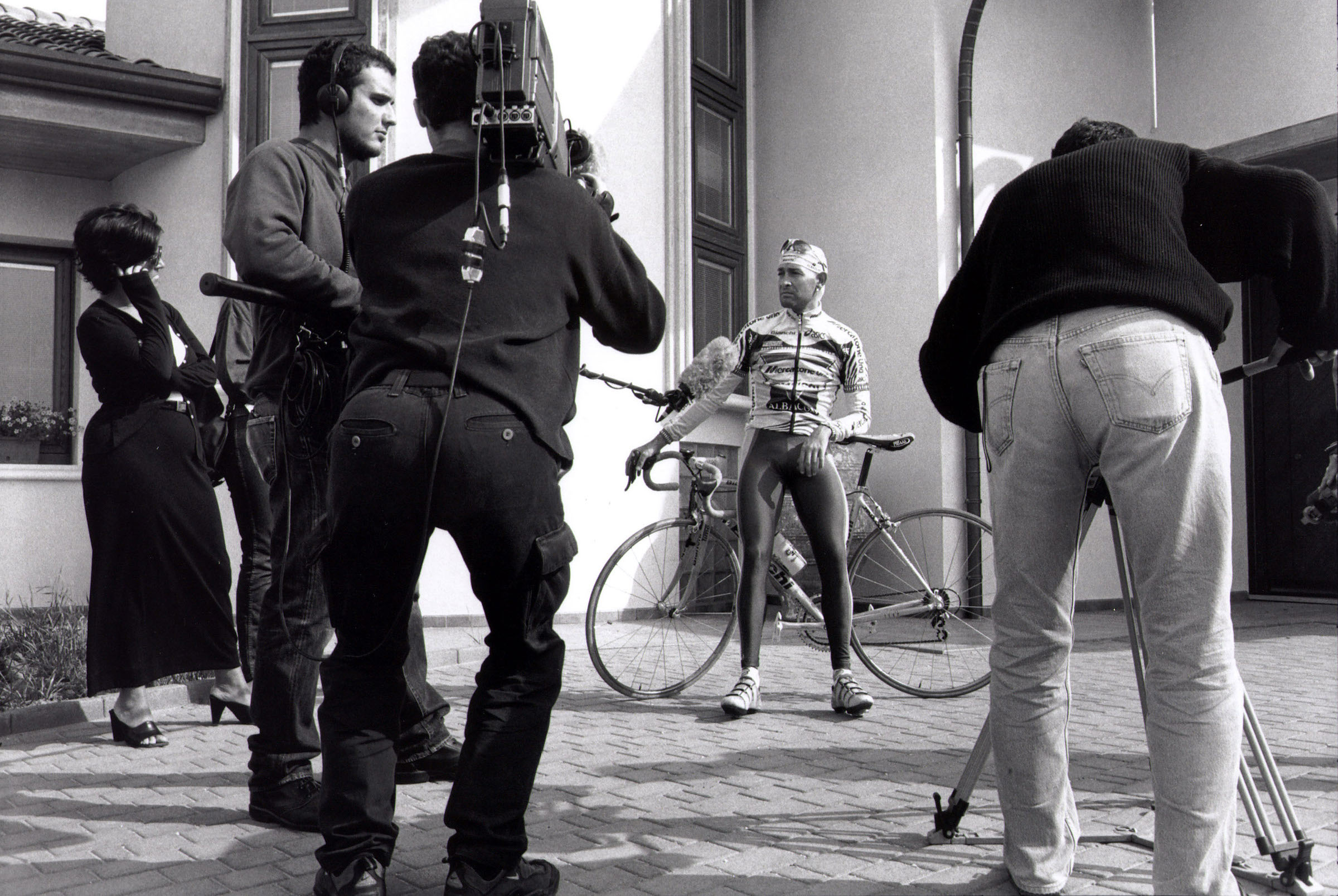

On the other side, it’s much darker, the gloom heightened by the Nosferatu-shaped shadow cast by the figure in the doorway, elfin, a bandanna covering his bald pate, a large earring hanging from each ear, very much living up to his alter ego, ‘the Pirate’.

This is the picture that is generally painted when analysing the fortunes of Italian cycling following the death on Valentine’s Day in 2004 of Marco Pantani. When he was in his pomp in the mid-1990s, Italian cycling was still surfing a wave of popularity that had carried it from the first years of the 20th century.

In 1998, when Pantani claimed the first leg of the Giro-Tour double, no fewer than 13 Italian teams lined up in the corsa rosa, while half a dozen Italians representing six different squads finished in the top 10.

Fast forward 21 years to the Giro’s latest edition, and the comparison is stark: just three Italian teams on the start line, each of them present thanks to a wild-card invitation from the race organiser RCS, and just one Italian finisher in the top 10, almost inevitably Vincenzo Nibali, the nation’s unquestioned standard-bearer for the past decade.

Yet, despite victories in all three Grand Tours as well as both Italian one-day Monuments, the Sicilian has failed to evoke the same interest and fervour as Pantani, who has become a mythical figure, one who has been lionised for feats that are remembered by memorials on the climbs where he shone brightest.

“We must ask ourselves why we still talk about him,” mused former La Gazzetta dello Sport journalist Marco Pastonesi following the publication of his book Pantani era un Dio (Pantani was a God). “We still talk about him because he was the last to provide real emotions. There is still talk of him because he was physically ugly, small, hairless and clumsy on a bicycle and he won. Alone against everyone.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

>>>>Need a new challenge for 2020? Join the CW5000 community and inspire your riding

There is still talk of him because during his career he had many injuries and accidents and he always came back, and as a winner. Until that moment when he finally failed to get back up.”

This analysis may seem overblown, but Pastonesi is one of the most astute observers of the Italian cycling scene, and it chimes with that of other journalists. “When you go to Italy and get into a taxi or go into a hotel and they ask you why you’re there, when you say you’re there for a bike race they quickly mention Pantani but don’t really have any knowledge beyond that.”

“They’ll say, ‘Yes, I loved Pantani…’ For the lay public as far as cycling goes it’s almost as if the clock stopped on the sport with Pantani,” says writer and podcaster Daniel Friebe.

Read the full article in this week's Cycling Weekly magazine. In the absence of the action from the Giro we've dedicated the issue to Italian cyclists, bike builders, designers and imagery. You can subscribe to Cycling Weekly and get the magazine delivered to your home every week, or buy from your supermarket or newsagent.

Editor of Cycling Weekly magazine, Simon has been working at the title since 2001. He first fell in love with cycling in 1989 when watching the Tour de France on Channel 4, started racing in 1995 and in 2000 he spent one season racing in Belgium. During his time at CW (and Cycle Sport magazine) he has written product reviews, fitness features, pro interviews, race coverage and news. He has covered the Tour de France more times than he can remember along with the 2008 and 2012 Olympic Games and many other international and UK domestic races. He became the 134-year-old magazine's 13th editor in 2015 and can still be seen riding bikes around the lanes of Surrey, Sussex and Kent. Albeit a bit slower than before.