Record rides: John Woodburn’s record breaking End-to-End, 1982

Eighties hardman John Woodburn talks about his epic End-to-End feat

Photo: Cycling Weekly Archive

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

"The old man’s back,” John Woodburn announced to the ragtag army of helpers, friends, sponsors, journalists and Road Records Association officials who had followed him for 848 miles over the last two days and two nights.

Journey’s end for the weary but jubilant group was the faded lounge of the John O'Groats House Hotel, a wedding-cake-like Victorian folly whose whitewashed Baronial towers and crenellated battlements had failed to protect the resort against a gradual decline in visitor numbers to mainland Britain’s most north-easterly point.

>>> 28 things you’ll only know if you’ve done Lands End to John O’Groats

The date was August 15, 1982. It was just after seven o’clock on a Sunday morning. The years may not have been kind to the hotel whose desolate car park hosted the finish line, but its VIP guest seemed immune to them.

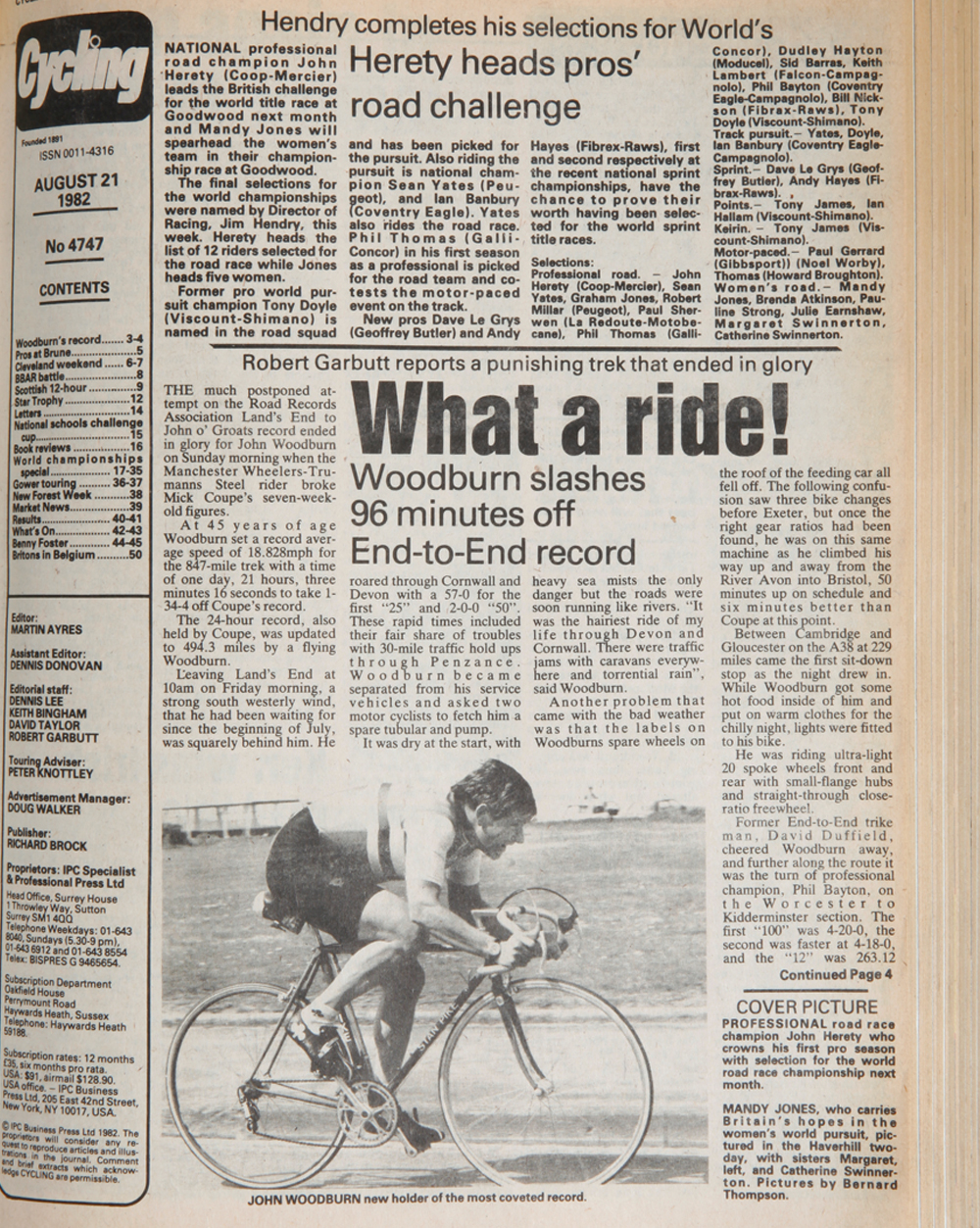

At 45 Woodburn had just become the oldest ever breaker of the Land’s End to John O'Groats record. Victory was all the sweeter because the previous year he had tried and failed to break the record and a newcomer, Mick Coupe, had sneaked in and set a new mark. In an awe-inspiring display of speed, strength, determination and bad temper, Woodburn sliced 96 minutes from Coupe’s time.

The last 60 years of the End-to-End

1958: Dave Keeler - 51hr 9min

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

1958: Reg Randall - 49hr 58min

1965: Dick Poole - 47hr 46min

1979: Paul Carbutt - 47hr 23min

1982: Mick Coupe - 46hr 39min

1982: John Woodburn - 45hr 3min

1990: Andy Wilkinson - 45hr 2min

2001: Gethin Butler - 44h 4min

Facts

First formal attempt: 1886 George Mills 121hr 45min on a penny-farthing.

First under three days: 1908 Tom Peck 70hr 42min (stood for 21 years).

This was a moment for Woodburn to savour. His ankles had swollen painfully — a flare-up of an old Achilles tendon problem — forcing him to abandon his plan to remount his blue Stan Pike bike and take the 1,000-mile record, but he didn’t care. He was happy with what he’d done, but he didn’t smile because John Woodburn doesn’t smile — he just glowers slightly less.

>>> 13 ways to increase your average cycling speed

The old man was back and he wasn’t going away any time soon. Woodburn’s record stood for 14 years, until 1996, when Andy Wilkinson stole it by just 57 seconds, and the current time of 44 hours, 4 minutes and 20 seconds, set by Gethin Butler in 2001, is barely an hour faster.

Tireless competitor

Only now, at nearly 79, is Woodburn thinking about hanging up his wheels. His career started a long, long time ago. He won the National 25 in 1961, aged 23, the first to win a championship on gears rather than on a fixed wheel.

>>> Are you using your bike’s gears efficiently?

Two years later he raced on the other side of the Iron Curtain for a Great Britain team in the Peace Race, where he finished 14th. In 1978 he became the first over-40 veteran to win the British Best All-Rounder competition and in 1981 he beat the Bath-and-back record.

He was still breaking records in time trials into his 60s — he rode a 51-minute 25 at the age of 63, a record still unbeaten. At 73 he rode a 21-minute 10, another one that still stands.

>>> “I regret that I didn’t train like I did in my 40s earlier in my career” (video)

Perhaps that’s why when you ask him now, Woodburn doesn’t consider his 1982 Land’s End-John O'Groats record to be one of his standout rides.

Woodburn is brutally honest when he describes how the End-to-End came about. At the time Manchester Wheelers was more than just a club. Its sponsor, steel magnate Jack Fletcher, who recruited the best time triallists in Britain regardless of where they lived, ran it as a business.

Get your pacing right

It was Fletcher’s idea for Woodburn to attempt the End-to-End. Woodburn, however, wasn’t

so enthusiastic.

“I’ve done so many different things that I could have just said, ‘I’m not doing that — I’ve got better things to do than sit on a bike for two days,’” he says. “But it was the number-one thing to do. I was getting bloody old and I just wanted to get rid of the thing.”

>>> How to fuel for long distance rides

Woodburn speaks in a gruff Brummie hybrid that splices in the elongated vowels of the West Country. Born and raised in Birmingham, he followed his father to Berkshire where he spent his non-cycling career working as an engineer for the Post Office.

Next he dismisses Lands End-John O'Groats itself. “There’s not a lot to it. You can’t go too quick at the start,” he says.

However, as Woodburn concedes in Ray Pascoe’s film of the attempt, Two Days and Two Nights, he started training seriously on January 1, 1982, building to 60 miles each evening after work, then 100 miles on Saturday and another 100 on Sunday. When the racing season started he rode the longest local time trials on the calendar to build speed.

>>> Five invaluable tips to help you step up from riding 60 to 100 miles

By the end of July 1982 Woodburn was ready — or “fairly fit” as he puts it. “You’ve got to be fairly fit but you don’t want to be bloody killing yourself. You’ve really got to make sure you can keep going and get to the other end, so it’s pretty simple really.”

The wind, however, did need to be blowing. By mid-August a strong enough south-westerly had got up so Woodburn and his team headed to Land’s End. On the morning of Friday August 13 they were ready to go. The feed car, the silver Volvo 145 estate of Keith and Brenda Robins, was crammed full of food. Spare wheels and a spare bike were mounted atop two more cars, a red Chrysler Alpine and a gold Cortina Estate.

At around 10am timekeeper George Hunton checked his watches and the countdown began. Woodburn took up his position outside the front door of the Land’s End Hotel beside a parked Wall’s ice cream van and a blue Ford Escort.

>>> Jens Voigt: Life lessons from 30+ years of riding

As the pusher-off balanced him, all went eerily still for a moment. The only movement was the rising and falling of the white horses in the sea behind. With 10 seconds to go Woodburn’s wife Anne ran forward to zip up her husband’s Manchester Wheelers wool jersey — a tender moment akin to a kiss for luck since Woodburn does not do soppy — and he was off, out of the saddle winding up a big gear, looking for all the world as if he was starting a 25-mile time trial on his local Maidenhead course.

Time trial pace

With the wind behind him, Woodburn actually was riding at time trial pace, covering the first 50 miles in two hours dead, despite holiday traffic at Penzance and losing his following cars.

This caused him to miss a feed, which annoyed him and, to add to the confusion, a rainstorm had washed the labels off the spare wheels on the car roof. He was given a wrong wheel when he asked for a change for the early sharp gradients.

>>> Four tips to nail any climb (video)

For the flat sections he used a close-ratio straight through block (a six-speed Maillard ‘13-up’) with a bottom gear of 42x18, and for steeper hills he had a wheel with a 20-tooth sprocket. Fortunately then, as now, Anne managed to exert a calming influence on Woodburn.

In Pascoe’s film, Anne Woodburn and Keith and Brenda Robins look efficient but relaxed. The big Volvo had been converted into a mobile larder and the tailgate lifted to reveal stacked baker’s crates, with kitchen roll rigged on a length of bungee in the offside rear window and a gas stove in the nearside.The rear bumper doubled as a kitchen counter.

>>> Back from the brink: riding again after a stroke

Whenever Woodburn took one of his brief stops for a sit-down meal — the first 10-minute stop was near Tewkesbury at dusk on the first evening — a picnic blanket was already laid out on the verge, polystyrene cups full of mince and bidons for cold drinks stood in an orderly arrangement. Dry jerseys and shorts awaited and Woodburn was massaged vigorously while he stripped off.

Fuel right, ride well

However, Anne Woodburn reveals that keeping her husband fed and watered was in reality incredibly stressful.

She shared the driving and feeding with the Robinses and for them it was certainly no picnic: “Staying awake for two days… you can’t say it killed them, but they were close to divorce in the back of the car for two days while I was driving.”

>>> Listen to your body: don’t ignore the warning signs of injury

The RRA rules forbade the feed car from overtaking its rider more than once every half hour. If the feed car or one of the others wanted to get ahead of the rider more often than that, it would have to take another route. These detours could result in frantic chases through back lanes in the dead of night.

Former Cycling Weekly editor Robert Garbutt, who travelled with the Woodburn cavalcade, wrote in his report: “Former End-to-End trike record holder Pat Kenny (travelling with the support team) was a master of these detours on Woodburn’s ride and upset courting couples as he and his companions blasted down quiet country lanes late at night to get in front of their man and hand up drinks and sponges.”

>>> How to resume your training after a break

By the evening of the first day Woodburn had already had enough of his prix fixe menu and decided to go à la carte. He asked for fried fish. “So Keith and I found a fish and chip shop in Stafford,” Anne recalls.

“But it was 10 or 11 o’clock on a Friday night and there was a queue. I went to the front and said, ‘Look, I’m really sorry but…’ and luckily the man in the chip shop had been listening to local radio and heard about the End-to-End. He said to the queue, ‘You’ll just have to wait because this person is very important.’”

>>> Watch: Mark Beaumont’s epic non-stop ride around the north of Scotland

“You get very bored with what you can eat on a bike,” interjects Woodburn. “You need to be able to eat going along and it’s not easy. Normally you don’t ride the bike all bloody day long and try to eat at the same time.”

Pass the brandy

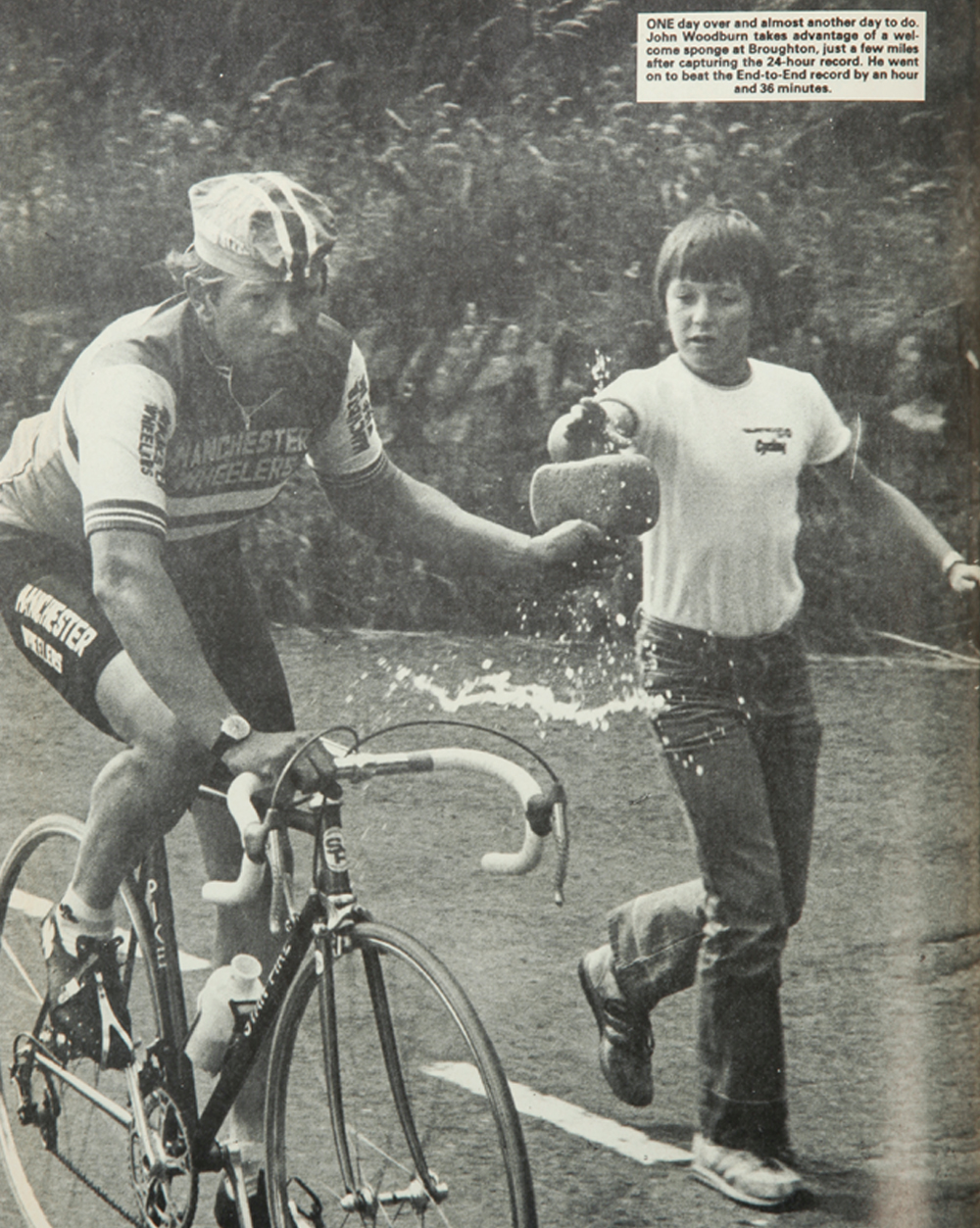

Twenty-four hours in, Woodburn was at the start of the Lockerbie bypass having covered 494 miles — ahead of Coupe’s mark. At Blair Atholl, Woodburn passed the point where he had abandoned a year earlier, struck down by a virus.

At that point Woodburn was going through a rare bad patch during which he managed just 11 miles in 45 minutes. But for the team the back, if not the record as yet, had now been broken.

>>> It’s never too late: taking up racing as a veteran

“He was still on schedule,” wrote Garbutt, “and on the long, straight climbs of the A9 he slowly recovered, topping 1,500 feet at 674 miles. Night clothes were put on hurriedly at 8.15pm as helpers were attacked by midges.”

For the final miles Garbutt reports that “a flask of brandy was given up”. Was that a good idea? “Well, I’d had every other bloody thing,” Woodburn retorts. “No it wasn’t,” insists Anne sensibly.

Nevertheless, Woodburn stayed awake, rode his bike in as straight a line as he could manage, swooped into the John o’ Groats House Hotel car park and screeched to a halt in front of the wall of the public bar with the record his by over an hour and a half.

>>> Detraining: The truth about losing fitness

Unlike the overcast, windblown start at Land’s End two days previously, which had given way to torrential rain, it was a crisp, blue morning. An armchair had been placed outside the front door of the hotel for Woodburn to recover in, and a tartan blanket was wrapped around his shoulders — a Highland laurel wreath for the godlike victor in an unimaginably arduous competition.

Thirty-three years on Woodburn grimaces at the memory. “I’ve always tried to do the best I can, go as fast as I can,” he concludes. For him averaging just under 19mph for 848 miles was all in a day’s — or rather two days’ — work, but for the purist Woodburn’s End-to-End is the equivalent of Eddy Merckx’s 1972 Hour record. No aerodynamics, no scientific training or nutrition and certainly no drugs. Just a lightweight steel bike and sheer bloody-mindedness.

>>> Tips for cycling and training in the dark

Woodburn, getting impatient and in any case too modest to hear any such blandishments, now wants to change the subject. “London to Bath and back, that was one I was happy with because it was Les West’s record…” he begins.

The making of Two Days and Two Nights

“I don’t think the record had ever been filmed before,” remembers Ray Pascoe. “So I drove down to Land’s End with my girlfriend at the time and a 60mm cine camera with some film, and I filmed it wherever I could get in. It was very difficult because you had to play the game [RRA rules] — no overtaking.

“The day before he started I asked John if he’d just ride up and down the road in his racing kit for me so I could get some nice close-up shots as I wouldn’t get them once the actual attempt started. So he did, and I’ve used it in the film. Afterwards he was worried that people would think that was part of the attempt and that he’d get disqualified. That was the only time I could ask him to do something for me, as you don’t speak to a rider during the attempt.

“John was very pleased with the film. I showed it to him when I was cutting it. He came up to my Wardour Street office and he was very pleased it had been filmed, but nothing happened until I had decided how I would put the film together. I met a guy called Pete Dansie, who had ridden with Woodburn and Alf Engers. Dansie was a film editor and he came into my office when I was at Shepperton Studios and saw a copy of Cycling Weekly there and said, ‘Oh, are you into cycling?’ So I showed him the John film and he said, ‘Right, let’s put it all together and put it out on video,’ so we did.”

Two Days and Two Nights is available at bromleyvideo.com or via the Cycling Weekly shop.

Simon Smythe is a hugely experienced cycling tech writer, who has been writing for Cycling Weekly since 2003. Until recently he was our senior tech writer. In his cycling career Simon has mostly focused on time trialling with a national medal, a few open wins and his club's 30-mile record in his palmares. These days he spends most of his time testing road bikes, or on a tandem doing the school run with his younger son.