How do bike gears work? A simple and detailed explainer for beginners and intermediates

If you don't have a clue how many gears your bike has (let alone how to use them!) we've got you covered with this simple explainer. For more depth, just keep on reading

Luke Friend

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Knowing how the gears on your bike work will add enjoyment to your riding. By understanding the fundamentals you’ll be able to better select the right gear for the right terrain, which will help you to maintain an efficient pedaling cadence on both climbs and flats, whether you’re looking to keep pace on a club run or you're out for a relaxing solo ride.

This knowledge can also help you choose the right gearing set-up for you. In this article we’ll cover the basics of a typical road bike groupset whether it’s Shimano, SRAM or Campagnolo. We’ll break down the differences between the various chainset types, that's the big ring or rings by the cranks, as well as looking at gravel bike variations, including 1x set-ups, and options such as hub gears. We’ll also dig into the variables of 10, 11, 12 and 13-speed groupsets to help you decide which is best for your riding.

But first let's start with the basics.

How do gears on a bike work: the basics

What determines the number of bike gears you have?

It’s a simple multiplication of the number of sprockets at the rear with the number of chainrings at the front. If your bike has two chainrings and a 12-speed cassette then you have 24 gears. If you have two chainrings and an 11-speed cassette, that would be 22 gears. If you have a triple chainring and an 8-speed cassette, that would be 24 gears - and so on.

Why do you need gears on a road bike?

Why have gears at all? Well, in a nutshell, gears are there to enable us to maintain a comfortable pedalling speed (or cycling cadence) regardless of the gradient or terrain - something that no one single gear is capable of.

A high gear, sometimes referred to by cyclists as a ‘big gear’, is optimal when descending or riding at high speeds. The highest, or biggest gear on a bicycle is achieved by combining the largest front chainring with the smallest rear sprocket - expressed as ‘50x11’, for example.

Vice versa, combining the smallest front chainring with the largest rear sprocket size results in the lowest available gear - which will help you keep the pedals spinning when the road points steeply up.

Let’s be clear about one thing - having lots of gears is not about making the bike faster. A bike with 30 or more gears is not an indication of a machine designed to break the land speed record any more than a bike with only a single gear (assuming similar ratios).

It’s about efficiency and having a much broader range, or choice, of gears for a given situation. Just like a car, bicycles benefit from a low gear to accelerate from a standstill, or to climb a steep hill. At the other end of the scale, a high gear helps you to achieve high speeds without over-revving.

Continuing with the car example, using too low a gear at high speed would result in high fuel consumption. The same is true of your body pedalling a bike. So, quite simply, more gears means more scope to find your preferred pedalling speed.

To put this into perspective, in the days of nine-speed cassettes, a range of 11-28t teeth could only be achieved by having sizeable gaps between sprocket sizes. Modern 12 and 13-speed cassettes have a full three or four extra sprockets to plug those gaps with - making for a much smoother progression.

Having smaller gaps between gears means the possibility is there to greatly improve pedalling efficiency. You should be able to fine-tune your pedalling speed to suit the gradient or terrain, often resulting in a lower energy cost.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You'll also likely experience more precise shifting, as the mechanical difficulties the chain has to overcome to climb onto the bigger sprocket or drop down onto a smaller one are much reduced with smaller increments.

Why do some people opt for a single speed bike?

You don't have to ride a bike with multiple sprockets and a variety of gears - some people choose to ride singlespeed bikes. These still have a gear - a single gear - which is determined by the size of the front chainring and rear cog.

Singlespeed bikes are popular among commuters living in flat areas, because they require little maintenance. They're also used by some racers (hill climbers for example) who want to drop weight and cut down on any extra complication coming from the shifting process - in this case, choosing the correct gear ratio is crucial. Finally, track bikes only ever have one gear - though again riders will change their set up to suit certain events.

Win some, lose some

The reality, on a multi-geared set-up - particularly when there are as many as 33 on offer - is that ‘overlapping’ gears are unavoidable. In other words, some gear combinations will result in the same ratio as others using a different sprocket and chainring. For example, 53x19 is the same gear as 39x14.

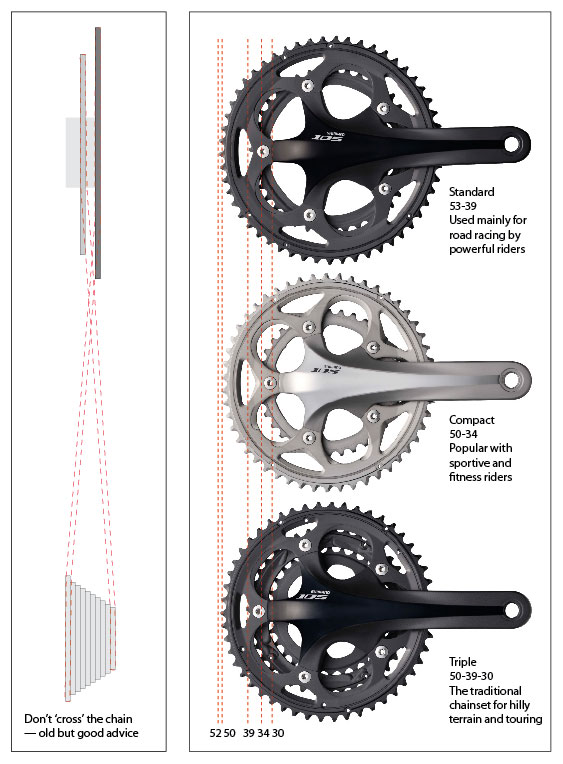

Also, certain ‘crossover’ gears, at the extremes of the range, may not be recommended for use, due to the additional strain that is placed upon the chain. Old-fashioned advice, which is still relevant, is to avoid ‘crossing the chain’. See the diagram below for an illustration of this.

However, as we’ve already said, the total number is not the selling point. Rather it’s the ability to have such a continual progression of closely spaced gears that will make your pedalling more efficient.

Today there's no need to struggle thanks to the extensive range of gearing options available that allow cycllists of all abilities can get the most from their pedalling. But how do you determine what will best suit your riding? Here’s the lowdown to put you on the right track.

Guide to different types of bike gears and how they work

Standard double

A 'standard double' means two chainrings at the front paired with up to 9, 10, 11 or 12 sprockets at the rear.

Traditionally a classic 53-39t combination is known as a 'standard' chainset, though these days it's largely unused by recreational cyclists and very rarely specced on bikes by manufacturers.

However a standard double set-up is still often the preferred choice for racing, offering the largest chainring sizes for the biggest gears possible to keep you pedalling smoothly when speeds are high.

Some reduction of the lower gearing is possible, but only as low as a 38t inner chainring, so if it’s low gears you’re after, a standard double is not the best way to go.

Compact

A compact is essentially a double set-up, only smaller. Both chainrings are reduced in size, usually 34t or 36t inner, paired with a 48t or 50t outer, reducing the gear ratio across the range. SRAM uses a 13-tooth differential in its chainsets, so its off-the-peg compact options are slightly different, and we'll discuss these later.

Understandably a compact is a highly popular choice. The reduction in gearing at the lower end is enough for most to tackle even long and steep Alpine climbs, especially when paired with a 32t cassette. Vitally there isn't a huge reduction of the top gear, which still allows for fast descending and speed on the flat.

Semi-compact

Semi-compact chainsets surged in popularity in the last decade or so, and they are usually the go-to front chainring combination for race-oriented bikes sold with a Shimano/Campagnolo double-ring setup.

The semi-compact chainset offers a 52t outer chainring (one tooth smaller than the standard, but two teeth bigger than the compact) paired with a 36t inner ring (three teeth smaller than the standard and two bigger than the compact).

This combination offers the best of both worlds; the 36 inner ring can be paired with an 11-28, 11-30 or 11-32 cassette at the rear to offer enough gears to tackle almost every climb, while a 52t at the front offers a bigger gear for fast group riding, descending, and even racing.

Triple

You don't often see a triple crankset these days. Where you do, they tend to be on a hybrid bike or a touring bike. The benefit of a triple crankset is that they provide a wide gearing range without the need for so many sprockets on the cassette, making them a much cheaper and rather more robust option. The tiny inner rings tend to allow for a smaller bottom gear that you would typically get on a double crankset, too. If you plan on doing any loaded touring then this remains a great option.

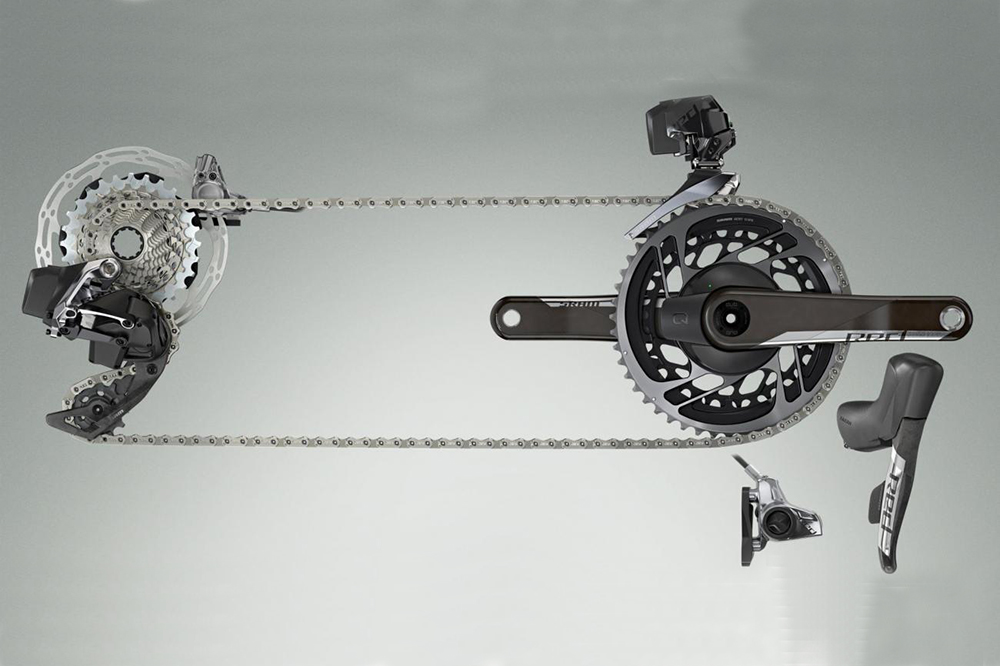

SRAM AXS

In 2019, SRAM launched its AXS groupset. Available as SRAM Red eTap, Force, Rival, and Apex the groupset offers smaller chainrings: available options are 50/37T, 48/35T, 46/33T and even a 43/30T in both the Force and Rival builds (this 'wide' option requires a 'wide' front derailleur to match).

On the back, the 12-speed cassette starts at a 10-tooth sprocket, and proritises keeping the jumps small between the smaller sprockets, then balancing that out with larger jumps between the bigger sprockets, to provide a wide overall range. The benefit of this is that you have small changes in cadence when riding hard and fast on the flat but plenty of lower gears when the road points up. Here the larger jumps are beneficial allowing you to shift into easy gears as the gradients increase.

The SRAM Red eTap AXS groupset with its innovative gearing ratios

1x or single chainring

For years a single chainring was the preserve of track bikes or beach cruisers. But no more. Popularised by SRAM, but also offered by Shimano and Campagnolo 1x set-ups are now seen in larger numbers. These pair one chainring with a multi-speed cassette, typically 11, 12 or in recent years, 13-speed.

Favoured for their simplicity, they eschew the need for a front derailleur and make shifting gear a straightforward choice of either going up or down the cassette. To ensure the chain remains in place despite the lack of front mech, special chainrings have been designed for 1x usage, as well as rear derailleurs featuring a clutch mechanism.

Because of this they’ve become a favourite of gravel riders, where chain retention is vital and bigger gear jumps less problematic. Indeed, Shimano and Campagnolo 1x offerings are gravel-specific; Shimano’s GRX groupsets are available as 1x, while Campag’s Ekar is a 13-speed system. This year, SRAM has followed suit and updated its Red AXS 1x groupset to 13 gears, perhaps a precursor to its entire family of 1x groupsets gaining an extra sprocket.

But a 1x groupset isn’t just for gravel. If you race crits, for example, or ride predominantly on flat terrain it could be a great option. Indeed, some SRAM-sponsored WorldTour teams have experimented with single chainring set-ups for certain races or stages, allowing them to maintain an optimal chainline. And at the other end of the spectrum, the simplicity makes them ideally suited to cycling newbies.

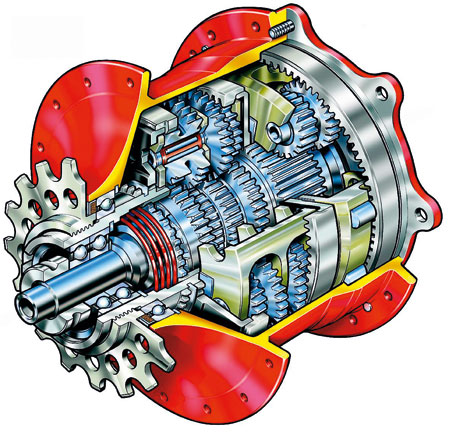

Hub gears

This type of robust, low-maintenance planetary gear system, housed in a fat rear hub, is still going strong. The popular Rohloff hub has 14 gears, while four, seven, eight, nine and 12-speed options are available from the likes of SRAM, Shimano and Sturmey-Archer.

The choice of individual gears may be less than using a derailleur system, but it’s still possible to personalise ratios by playing around with chainring and rear sprocket sizes. Hub gears are generally tough and require very little maintenance so they’re great for everyday commuter bikes, especially as most allow you to change gear without pedalling too - handy at traffic lights. Their weight is their Achilles heel, counting against them in hillier terrain and on endurance rides.

In 2019 Classified, a Belgian tech company, released its Powershift system, a wireless electronic hub system that now (since 2021) boasts 24 gears and instant shifting, even under load. The hub does require your wheelset to be compatible but there is a growing number of wheel brands who are now offering a Classified option. It's even been used in WorldTour races.

How do road bike gear shifters work?

With some modern designs, it’s not always immediately obvious where the shift levers are. If you’re in any doubt, a local bike shop will run through this with you, but here’s the basics for the majority of the mechanical groupsets that are on the market. Regardless of brand, right-hand levers control the rear derailleur, and left hand levers the front.

Electronic gears often work differently, and some like SRAM AXS and the latest iteration of Shimano Di2 can even be customised to the rider's preference.

How does electric road bike gear shifting work?

Shimano Di2

Shimano's electronic Di2 groupsets - Dura-Ace, Ultegra,105 - work with a button system, but with the same principle as the mechanical shifters. The left shifter operates the front derailleur, and the right operates the rear.

There are two buttons behind the brake lever on each shifter. On the left the slimmer dimpled inside button will shift the chain up from the small ring to the big ring. The smooth paddle-shaped outer button below will move the chain down from the big ring to the small outer ring.

On the right shifter, the inner dimpled button will move the chain up the cassette to easier gears, while the smooth outer button will move the chain towards the harder gears if you're riding faster.

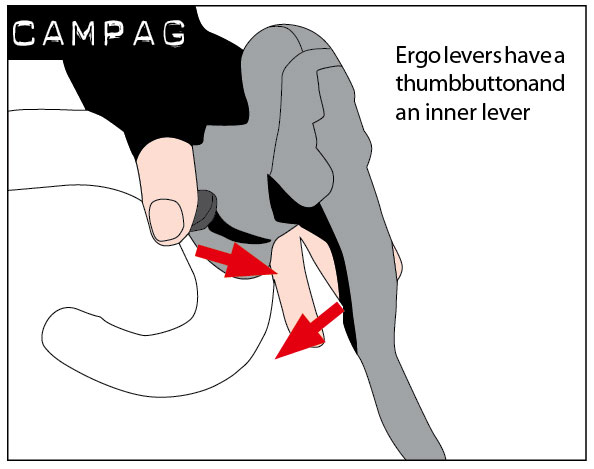

Campagnolo Super Record EPS

Like its mechanical cousin, Campagnolo Super Record EPS shifters feature a button behind the brake lever and a thumb button inside the shifter hood.

On the right-hand shifter the button behind the brake lever will move the chain up the cassette into an easier gear. The thumb button will do the opposite and move the chain into a harder gear at the rear. EPS also offers multi-shift, so if you hold the button down the chain will shift multiple gears until you release the button.

On the left-hand shifter, the paddle button behind the lever will move the chain from the inner small ring to the larger outer ring. The left-hand thumb button will do vice versa.

This year Campag has also introduced Super Record WRL, a wireless groupset that sees the Italian brand drop the thumb buttons for those more inline with Shimano and SRAM's shifter buttons.

SRAM AXS

SRAM eTap AXS - the Red, Force, Rival, and Apex groupsets - work in a different way to the mechanical SRAM groupsets and the competing electronic groupsets.

As previously mentioned, SRAM AXS shifting setup is customisable but the default setting uses just two buttons. The right-hand paddle button, behind the brake lever, moves the chain into a harder gear on the cassette. The left-hand paddle button moves the chain up the cassette into an easier gear.

To move the chain between the two front chainrings, the rider simply needs to push both the left-hand button and right-hand button at the same time and the chain will move up or down depending on its starting position.

Glossary for understanding how gears on a bike work

- Chainring: toothed ring at the front end of the drivetrain, attached to the crank.

- Cassette: cluster of sprockets at the rear of the drivetrain, containing up to 12 gears, of various sizes.

- Block: another term for the group of rear sprockets, but really refers to the older, screw-on freewheel.

- Derailleurs: front and rear derailleurs do all the hard work of moving the chain from one sprocket (or chainring) to the next.

- Sprocket: refers to an individual gear within the cassette/block.

- Ratio: describes the relationship between sprockets and chainrings, for example ‘53x12’, or the sprockets on a cassette (11-28).

- t: short for teeth — to describe how many a given sprocket has — for example ‘23t’.

- Drivetrain: term grouping together all the moving parts that connect the crank to the rear wheel and hence drive a bicycle along — namely the chain, the cassette and the chainrings.

- Cadence: pedalling speed, measured from how many revolutions the crank makes per minute — expressed in RPM.

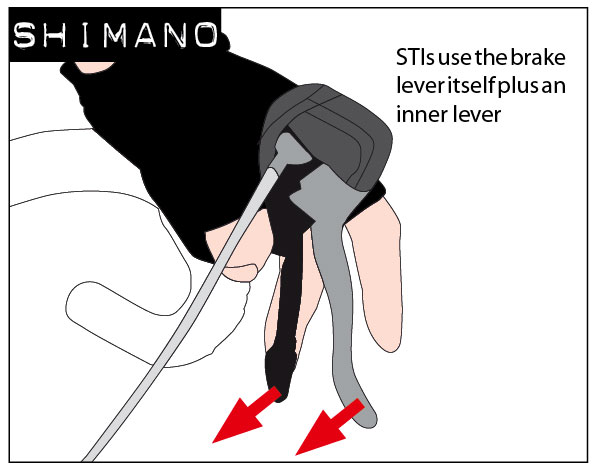

- STI lever: abbreviation of ‘Shimano Total Integration’ — a term for Shimano’s design combining brake and shift levers for road bikes, but often (mis)used generically to refer to the shift/brake levers regardless of brand.

- Ergo lever: Campagnolo’s name for its version of integrated gear shift and brake levers (ie Campagnolo’s STI).

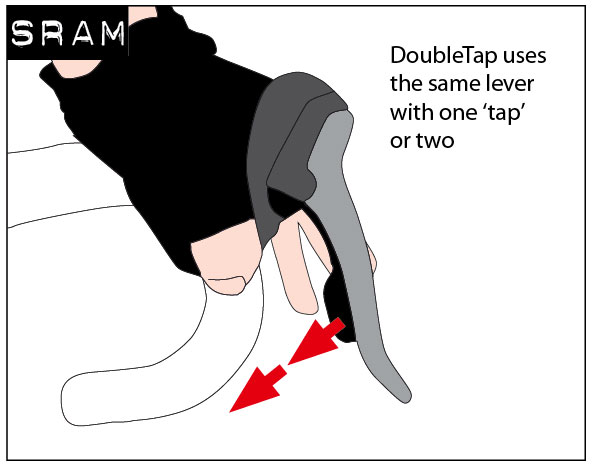

- DoubleTap lever: SRAM’s slice of the pie, in terms of shifter technology — uses the same lever for upshifts and downshifts.

Michelle Arthurs-Brennan the Editor of Cycling Weekly website. An NCTJ qualified traditional journalist by trade, Michelle began her career working for local newspapers. She's worked within the cycling industry since 2012, and joined the Cycling Weekly team in 2017, having previously been Editor at Total Women's Cycling. Prior to welcoming her first daughter in 2022, Michelle raced on the road, track, and in time trials, and still rides as much as she can - albeit a fair proportion indoors, for now.

Michelle is on maternity leave from April 2025 until spring 2026.

- Luke FriendFreelance writer