Stiffness vs. Compliance: Making sense of bicycle frame design

How frame designers find the sweet spot between stiffness and compliance as well as some thoughts on “ride quality”

The diamond shape of a bicycle frame hasn’t changed much since it was first invented. Triangles are an enormously strong shape and can also be easily modified to accommodate riders of different statures. Each rider’s needs may vary, but the essence of the design need not change drastically.

A well-built bicycle transfers power efficiently through the drivetrain, steers predictably and is comfortable to ride for long periods of time. Overemphasizing stiffness creates a bike that turns every variation in the road surface into numbing vibrations while focusing too much on compliance makes a bike that handles unpredictably and loses energy through undue frame flex. It is in the harmonious middle ground between these two extremes that good bicycles exist.

Ride quality as a concept is highly subjective. Furthermore, the sensations you feel while riding a bike cannot be easily attributed to any one component or part. In sum, one might feel some combination of the following while riding: tyre casing, air pressure, spoke and rim interplay, frame design, seatpost flex, saddle padding and condition of chamois (or lack thereof). And that’s just the rear half of the bike.

There’s a reason why many bike reviews focus on objective characteristics, like weight, geometry and aerodynamic performance. Trying to isolate the performance of the frame from the entire system is somewhat akin to trying to discern an individual thread in a sock with the bottom of your foot. Still, we try our best.

Some thoughts on flex

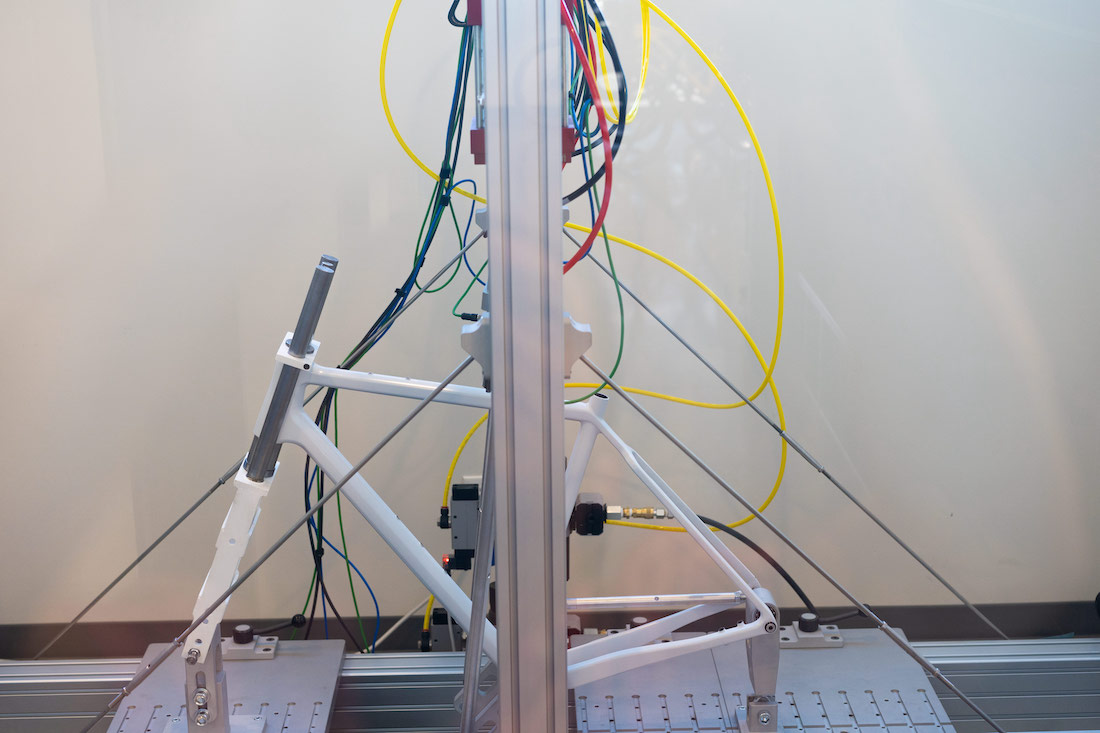

Stress testing being done on a frame as Argonaut Cycles in Bend, Oregon.

We spoke with frame builder Corey Lowe of Eyewater Bicycles to learn more about frame composition. Lowe started in the bike industry with Parlee Cycles as an engineer and frame builder, then moved to Cannondale and Specialized as a design engineer with the high-performance road team. He has also done contract engineering work for places like Allied and Cervelo and currently builds custom carbon bicycles under the Eyewater name.

Lowe emphasized that the frame “must always [be considered] as a whole. There are times when isolating a component helps get a clear understanding of its impact, but the end result of how a frame rides is very much a game of the whole package.” As he says, “It is relatively easy to add stiffness while adding weight. The trick is to add stiffness without adding weight. The material properties of carbon can be adjusted with the layup schedule without necessarily adding weight.”

We also asked him about balancing stiffness and compliance: “Frames can be designed for both objectives, improving one or the other using layup modifications. I try to design frames to meet the performance goals set out and then work to optimize ride quality and compliance from that point. These two parameters are not always mutually exclusive, especially with working with carbon layup schedules and round tubing.”

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Ultimately, Lowe says, “fit and geometry are the largest factors in rider comfort.”

Which tubes need to be flexible, and which need to be stiff?

Structurally, the highest concentration of stress on the frame occurs at the joints, especially the bottom bracket, with the middle of the tubes in between seeing the least amount of stress. The material used, its shape and its thickness all determine how it will react to strain and stresses.

If the goal of the design is to put the right amount of material in the right places, then this means using less material in the places where it will experience the least amount of stress.

With a conventional frame design, the downtube significantly affects the overall feel of the bicycle. It is the main structural element tying the bottom bracket to the head tube, so it is responsible for maintaining torsional stiffness and preventing too much lateral flex. If it’s too stiff, it won’t track the ground well, but if it’s too flexible, it will feel imprecise (i.e. scary) at high speeds or under heavy cornering loads.

The tricky thing to keep in mind is that the right stiffness for a rider is dependent on their size and weight. Chainstays need to be strong enough to hold the wheel in place while transferring the energy going through the drivetrain. The top half of the bicycle, particularly the top tube and seat stays, add to the strength of the whole by completing the triangles, but less rigid material here can help with finding the right balance of vertical flex.

The stiffness of the fork also significantly impacts comfort. Interestingly, the seat tube does very little to provide comfort or structure. Its primary purpose, outside of completing the triangles, is really just to place the saddle in the right position for the rider.

Methods

How does one change the stiffness of a tube? There are essentially three principles in play: material shape, thickness and diameter. Shaping is used both for aerodynamics and to encourage movement in specific directions and varying the thickness of the material at different points in each tube is used for weight savings and adjusting ride quality and rigidity. All else being equal, larger diameter tubes are stronger than smaller ones. By using thinner material with a larger diameter manufacturers can make bikes that are both light and strong.

There are also several other design elements to consider in addition to ride quality: aerodynamics, impact resistance, and weight all play a part, and depending on the application a designer may skew more toward the direction of one or more of these in order to meet specific aims.

Conclusion

Ride quality is an interesting topic of discussion in part because it is so subjective. What works for one rider may not work for another. Bicycles from large industry players are designed for those who fit within a certain range of constraints. Riders on either end of the height and/or weight bell curves will require adjustments to find a bike with their desired ride quality, and may need to seek alternatives to mass production offerings.

Ultimately, the biggest gains to be made when it comes to rider comfort are in the seatpost and tires. A seatpost designed to flex will remove much more road vibration than the frame, and ditto for tires: higher volume tires at lower pressures are key. When it comes to frame design, fit is the number one most critical element. A well designed-frame strikes a healthy balance between stiffness and compliance in order to fulfill its true purpose: making cyclists happy.

Tyler Boucher is a former (and occasionally still) bike racer across several disciplines. These days, he spends most of his time in the saddle piloting his children around in a cargo bike. His writing has appeared in magazines published in Europe, the UK and North America. He lives in Seattle, Washington.