Is 'women's specific geometry' a myth?

Every time one mainstream brand decides to eschew women's specific bike design, another comes out in favour. How can female riders navigate these conflicting opinions to ride away with a bike that fits?

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

This article forms part of a week of women's focused stories, in celebration of our Women's Special edition of Cycling Weekly Magazine, one sale from Thursday, March 10. See the full schedule of upcoming articles here.

The debate over women’s specific bikes has dragged on for well over a decade.

Women's specific geometry bike frames - typically with shorter top tubes and taller head tubes, designed to cater for claimed anatomical differences - have been around on the mass market since the early 2000s.

These frames were said to better cater for women's reportedly lower center of gravity, and trend towards carrying a greater distribution of muscle mass in our lower body.

Outside of the frame, women's bikes will have narrower handlebars and women's saddles - to meet the needs of women who have statistically narrower shoulders, and different saddle requirements.

The marketing argument

The creation of a women's specific bike also appeals to the shopping habits of the mass market.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Elsewhere in our consumer lives, women are marketed to according to their gender: most will buy a Venus razor over a Mach3. This means that the 'women's bike' aisle may feel like a more natural home. The difference within cycling is that being a male-dominated pursuit, choice tends to be more limited.

What do the big brands do?

It would be helpful if the bike manufacturers with the greatest access to data and research all took the same approach. However, if we look at Specialized, Trek, Liv and Canyon, what we’re left with is a raft of differing viewpoints.

Specialized and Trek were the first brands to create 'women's specific geometry bikes', with models arriving in 2002 and 2003 respectively. But both returned to unisex frame design around 15 years later, initially with women's models that featured gender-specific touchpoints, before these were replaced with one model to meet all needs.

Trek's Domane, Madone and Emonda models now have a unisex geometry, replacing the likes of the women's Silque, and Specialized replaced its Amira women's road race bike with a unisex Tarmac years ago now. Initially, it maintained the Ruby women's endurance bike, stating that these customers wanted a different experience compared to the male Roubaix shoppers, but the Ruby was axed at a later model launch.

Specialized, which owns the Retül bike fitting system, reportedly bases its "beyond gender approach" on data from 8,000 bike fits, "we’ve learned that all riders are unique, and that the stereotypes of body shape are largely inaccurate," the brand said at the time.

Meanwhile, Liv (the women's arm of Giant) is entirely dedicated to separate geometry for female riders. When I referred to 'unisex frames' at a recent bike launch, its founder Bonnie Tu looked told me: “those bikes are made for men, they’re not unisex.”

Liv says that its research papers show "significant anthropometrical differences that will determine the best bike fit", with its data placing women's legs as longer whilst our upper bodies and arms are shorter, proportionally vs men. It also says that "a woman’s percentage of lower body to upper body strength is greater than that of a man’s. We use this data on strength differences to tailor the stiffness and compliance of our frames to meet a woman’s power demands, without sacrificing the strength and durability of the frame."

Canyon takes a similar stance. The brand used 60,000+ data sets to determine its approach, concluding that women had a shorter wing span on average, so needed a shorter top tube to get the same ride quality.

“We position the women in the same way that we do men on a bike – taking into account the average differences between measurements," said women's brand manager, Katrin Neumann at the Canyon WMN road bike launch.

'No statistical difference'

The conflicting approaches above don't bring us closer to an answer. So what do custom bike fitters - who have no warehouses full of bikes to sell - feel the majority needs?

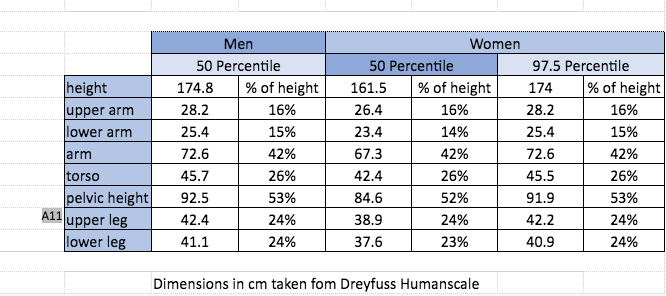

Bike fitting expert at VeloAtelier, Lee Prescott, tells me: “Based on the Dreyfuss Human Scale – the most comprehensive ergonomic data display there is – there’s no statistical difference between women and men’s limb lengths," not mincing his words, he reiterates: "There's no measurement which is different between men and women that affects bike fit.”

Numbers collected in the NASA anthropometric summary tell the same story, as do those produced by the USA Military database, based on 132 body measurements on around 4000 individuals.

It is worth bearing in mind that the anthropometric doesn't take into account flexibility, position on the bike, or the distribution of muscle mass.

"Women are typically more flexible than men - so to ride in an ideal position many female riders might actually have a slightly longer top tube," Prescott says.

Former lead physiotherapist at British Cycling, Phil Burt agrees that there's no statistical difference in limbs that required a differently shaped bike.

The founder of bike fitting services at 'Phil Burt Innovation' believes women are massively under served by the market - in terms of kit, saddles and more. But he doesn't think they need women's bikes; "I don’t think they [women's bikes] exist. Does a woman pole vaulter use a women's pole?"

"The only women's specific parameter is stance width. All bikes come with the same stance width [Q-Factor], all pedals except Speedplay, come with the same 53mm axles - but women have wider hips. So your Q-Factor is greater – which is why some women have knee pain, because their knee goes inwards as they pedal."

Small bikes for smaller riders

Despite being against women's specific geometry, Prescott does believe that shorter people - and taller people, anyone outside of the statistical norm - in general are not well served by the current market.

This is a position shared by frame builder Adeline O'Moreau of Mercredi bikes: “My personal experience with the men and women I’ve built bikes for is that the differences in reach and saddle to bar drop have all been to do with general fitness, and how much they stretch - it has nothing to do with your gender.

"What you find when you look at anthropometric data sets is that men and women have similar proportions, it’s just that more women are slightly shorter. What we need is more bikes for smaller people, not more bikes for women."

Many brands currently produce fewer bikes in small sizes - and sometimes the smaller bikes share moulds with larger versions - resulting in dramatic jumps in seat and head angle, and discrepancies in handling.

"If you're not producing many small bikes, the space between the steerer and the saddle needs to be as small as possible, so you can increase it by putting a longer stem on, or more setback on the saddle" says O'Moreau, "so you make a really steep seat angle, and a really shallow head angle. That means those bikes don’t handle well, but it’s a problem that affects everyone who is smaller – not just women.

“Off-the-peg manufacturers could make more smaller off-the-peg bikes – so the changes in top tube, or seat angle, would be less dramatic."

Many women's specific models have been designed around a shorter average height - and for that reason their handling can be more consistent.

One such selection is Canyon's WMN range, which provides for smaller riders in a way no other mass produced off-the-peg brand does (if we exclude kids' bikes): with smaller wheels.

The women's models range from 3XS (suitable for a rider or 152cm ) to Medium (186cm rider height), and the 2XS and 3XS bikes use 650b wheels, designed to alleviate the compromises made when attempting to design a small bike around the 700c standard.

“When you get to small sizes, if you’re using 700c wheels, you still need to maintain a certain distance between the two wheels, and between the crank and the front wheel to make it rideable. So you end up slackening the head angle, increasing the fork rake", says Canyon's Marketing Coordiantor Jack Noy.

"That pushes the front wheel back out again which solves the problem but affects the way the bike feels and affects the consistency of handling."

“By using a small wheel you gain the extra room, the size range increases and the consistency between the sizes stays the same,” he adds.

Prescott certainly supports this approach, “I would say smaller people are better served by 650b wheels. There is always going to be a rolling resistance penalty. But the smaller wheel allows them to get into a better position," he comments.

Also not covered by limb measurement stats is carbon layup.

Women's bike manufacturers often adjust the material to cater for a smaller individual producing less power and with a lower weight. This means lighter riders aren't forced to pay a penalty for stiffness they won't utilise, and it's something Canyon allowed for with its WMN range, creating the lightest bikes in its brand offering.

What should customers buy?

Test ride tips

Test riding a bike and not sure if it fits? Our tips...

1) Take your own saddle to a test ride, or ask to swap on something comfortable if you don't like the stock saddle - you can't base a decision on a ride if you weren't sitting comfortably

2) Ask for handlebars which suit your shoulder width to be fitted. Again, too wide or too narrow and you can't assess the handling of the bike. This might be tricky in the case of integrated cockpits, but you are making a big purchase.

3) Compare actual geometry tables before you turn up to test ride. Sometimes, the unisex and women's models genuinely use the same dimensions.

4) In an ideal world? Have a detailed bike fit on an adjustable rig before you start bike shopping - then you know exactly what sort of geometry will suit you as an individual.

The debate continues to drag on. Whilst one set of brands tones down its approach to female specific geometry, a new host of 'women only' machines arrive from their competitors.

Statistical differences in limb length appear to be downplayed by independent experts. However, none of the data sets used consider flexibility, riding experience, fitness or personal preference.

Regardless of limb length, height, weight and experiential desires - when all is said and done, the only person who has to ride your bike is you.

So the bike fitters, brands and custom builders can have their own debates. As a buyer, your best bet is to find the bike that fits you and your individual needs: that means test riding as many bikes as you can.

This article forms part of a week of women's focused stories, in celebration of our Women's Special edition of Cycling Weekly Magazine, one sale from Thursday, March 10. See the full schedule of upcoming articles here.

Michelle Arthurs-Brennan the Editor of Cycling Weekly website. An NCTJ qualified traditional journalist by trade, Michelle began her career working for local newspapers. She's worked within the cycling industry since 2012, and joined the Cycling Weekly team in 2017, having previously been Editor at Total Women's Cycling. Prior to welcoming her first daughter in 2022, Michelle raced on the road, track, and in time trials, and still rides as much as she can - albeit a fair proportion indoors, for now.

Michelle is on maternity leave from April 2025 until spring 2026.