Trailblazers: The exceptional women who changed UK cycling

In the saddle since 1922, the Rosslyn Ladies pioneered competitive women’s racing, and are still going strong today. Photographs: Daniel Gould and Rosslyn Ladies Cycling Club archive

It’s a sunny Sunday morning, there’s a slight breeze and it’s neither too hot nor cold — perfect conditions to be cycling on a club run.

In Ugley, Essex, one club is meeting for their regular get-together, but rather than lightweight, carbon frames lined up against the wall outside the restaurant where the members meet, there’s a trio of steel, retro steeds: a yellow Bates, a white Condor, and a blue Ephgrave.

>>> From Burton to Armitstead: Britain’s road race world champions

They belong to the Rosslyn Ladies Cycling Club, one of the UK’s first female-only clubs, established in 1922. At the time, women were not welcome at men’s clubs, so a bold group of female cyclists in Essex founded their own; the Rosslyn was born.

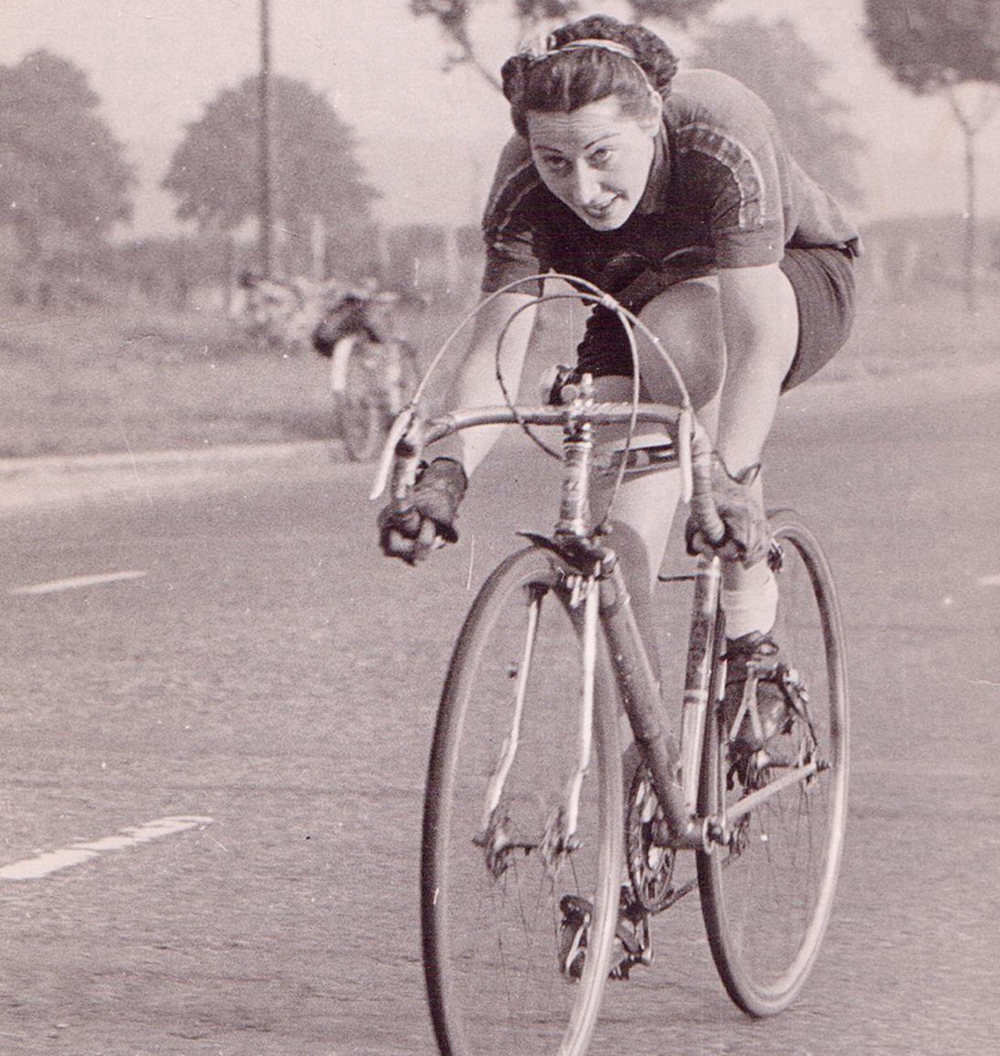

As well as giving women a place to ride socially, the Rosslyn Ladies were pioneers for women’s racing in the UK.

In 1924, the club promoted its first event, a 12-hour time trial, which made headlines four years later when it was turned into an open road event — the first of its kind for women. They paved the way for women racing on the track too, and promoted the first women’s track race at Herne Hill in 1927.

Today, most of the women in the club don’t ride a huge distance — most are aged 65 and over — but the 23 members meet once a month to reminisce, catch up and keep the spirit of the Rosslyn alive. On the day Cycling Weekly visits, the club is having its birthday lunch.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

>>> Aviva Women’s Tour and RideLondon included in new UCI Women’s WorldTour

Pat Seeger, club president, joined Rosslyn in 1946 aged just 20. She still has the bike her husband bought her in 1950, the yellow, fixed wheel Bates she used to race on, handmade from Reynolds 531 steel tubing.

Seeger is wearing a long-sleeved black top and matching leggings that the Rosslyn Ladies used to wear to race, with original cleated shoes.

“I had been riding a bit with my husband’s club. I left that because there were no girls who raced in it,” she says. “He was always reading about the Rosslyn... I lived in Highgate, London, so I used to ride across to east London.”

Seeger describes her eventful debut outing with the club. “On the very first run I went with them, it was lovely. There used to be about 20 out, all in twos.

>>> Three women’s WorldTour events planned for UK in 2016

“There were some youths coming [in the other direction] and they were saying very foul things. We all halted, Nellie [Cook] our secretary got off and she walked round and said, ‘wash your mouth out with soap’, [it was] very impressive. We were all laughing. I thought, this is a bit of all right.”

Whereas today the sight of a woman on a bike is commonplace, in the era between the World Wars, when the suffragist movement was still fighting for women to have the vote and equal rights, a group of women riding bikes, let alone taking part in club runs and racing, was far from the norm. In the early days of the club, members often had to contend with abuse.

Withstanding abuse

“It was greatly disapproved of,” says Seeger. “Nellie told me that, sometimes when riding back into London, [men] used to throw stones at them and things like that. I think it was especially [because they were] wearing trousers and that sort of thing.”

Iris Beauchamp, whose mother Flo Shamrock was one of the founder members, agrees: “[It was] so different really,” she says. “My mother, she had trousers and long socks — you just couldn’t show your legs.”

>>> Longo Borghini laments pay gap after winning just £871 at Tour of Flanders

However, rather than let this opposition stop them, the Rosslyn continued to make brave and bold decisions. One of the first club members once wrote: “We were jeered at in our breeches and long coats. We were called fast hussies… gradually the coats got shorter and eventually we

got more daring.”

Indeed, as the years passed, the club grew more daring in its wardrobe choices, and soon swapped long trousers for shorts on its club runs and social rides.

In fact, it was the shorts by which the Rosslyn Ladies were later identified. We meet two of the women’s husbands, who jokingly ask us about the shorts.

>>> “Cycling in Britain has never been in better health” says British Cycling president

“They were very short shorts for ordinary riders,” Seeger says. “Maisie, she was a professional machinist, and she could make us the most marvellous shorts, as short as you like, yet comfortable so they didn’t rub on the saddle,” says Seeger.

“We had all colours: I had some black and white checked ones, but also red and blue. We wore colourful jumpers or summer tops when it was hot.”

Early success

The club’s racing calibre rose rapidly in those early years, such was the ascendancy of women’s racing, and as word spread its membership swelled from 15 up to more than 50.

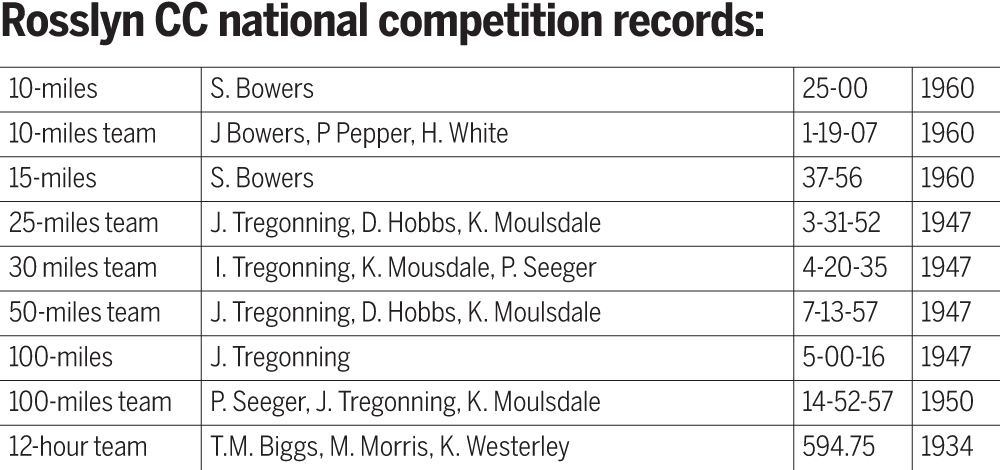

The club held its own series, the Rosslyn Trophy, in which riders competed over 25, 50 and 100 miles, and in a 12-hour time trial. Then in 1934 the club set the RTTC 12-hour time trial team competition record with a distance of 594.75 miles. More records followed into the 1960s.

Seeger was one of the Rosslyn’s most prolific time triallists and was part of the squad that set records in the 100 and 30-mile TTs. “I started racing and got in with the faster girls, and eventually I finished up in the team,” she recalls. “We had a great lot of successes.”

“It was a very fast team,” says June Grant, the club’s captain and a member of Rosslyn for 62 years. Seeger is modest about her individual times. “My best 10 was about 27-50, not all that fast,” she says.

>>> Petition to create national road race series for junior women generates big interest

“That was pretty fast!” Grant interjects. “Bikes were different in those days.”

“The top competition record time was about 25-50-something,” Seeger explains.

“At 25 [miles], my best was a 1-08-02, then again the top record was around 1-06, and my best 100 was four hours and 52 minutes, the record time then was about four hours and 37 minutes, which I think was set by Eileen Sheridan [in 1950] — she was a marvellous rider. She rang me up this week; we keep in touch, she’s 93 now!”

Unlike today when riders follow strict nutrition strategies to fuel themselves over long-distance time trials, in the Fifties there were no energy gels to stock up on.

Rather, when racing a 100-mile or 12-hour TT, riders had to stop mid-ride to visit feed stations where they’d find bananas, porridge and even rice pudding. This didn’t always end well.

>>> A look at the secret life of the cycle race commissaire

“Other than the drink stops, where we got drinks, sponges, I couldn’t [eat anything],” Seeger says.

“The first 12 I rode, Nellie our president was looking after me. She said there’s a food stop, and I was following the instructions and I got off. They had this very nice rice pudding. But when I got on again after, I thought, ‘I don’t think I should have had that pudding’ — I thought it had gone in my legs.

“I never did eat after I’d had that experience. Josie [another Rosslyn member] would have a big piece of cheese. I never felt hungry really, I was too strung up.”

Similarly, the club’s racing uniform in the Fifties and Sixties couldn’t have been more different to today’s. Like many pro riders in the modern peloton, the Rosslyn Ladies wore black kit, except it was nothing like modern skin-tight Lycra with aero credentials.

>>> 17 of the best international sportives to ride in 2016

Rather, the women were covered in long-sleeved black tops and long leggings, with a black cape available if it rained.

“I love all the clothing now,” says Seeger, who used to dye her clothes black to race in. “Our tights, if they got wet at the back, all sagged — horrible. You used to stand up on the pedals, and I always rode fixed wheel, so you’re doing this [mimes pulling leggings up] all the time trying to pull them up because the weight of the wetness just pulled them down!

“Jolly uncomfortable in the long-distance events!”

Camp Rosslyn

Life in the club was about more than just racing. A clubhouse was established in Ugley on the A11 time trial course, known as ‘camp’ where the members would stay most weekends when they were racing or marshalling at events.

“If people weren’t racing, they would be up there helping out,” recalls Seeger. “I never remember [there being fewer] than about 10 [in attendance]. It was a wonderful time.”

>>> Women’s cycling shorts: a buyer’s guide

After World War II, attitudes towards women changed, and Rosslyn members’ relations with their male counterparts were much more respectful. “After the war, it did seem to click, in that we could do all these things,” says Seeger.

“[The reaction from men] was positive. It was quite unusual to see all girls riding along together,” agrees Beauchamp. “[Men] appreciated the fact you were a cycling ladies club and that was that, and they had respect for you all.”

Part of the Rosslyn’s lasting legacy has clearly been the close relationships between its members, and the fact that for many it was more than just a cycling club; it was a way of life.

Many of the members had mothers who were in the club before them, or daughters who joined after, while a lot of them married men who were members of other cycling clubs.

>>> The best women’s bike saddles

Beauchamp was from a particularly cycling-crazy family. As well as her mother being a founding Rosslyn member, her father was Dave Marsh, amateur world champion in 1922 who also competed in the road race for GB at the 1924 and 1928 Olympics; her husband is former time triallist Eric Beauchamp, while both her brothers were cyclists and her granddaughter is also a member of the Rosslyn.

“We used to cycle everywhere with the club,” recalls Beauchamp. “We went at Easter to the Isle of Wight; we cycled all the way. We’ve been over to the Isle of Man for the racing; we cycled over to Liverpool,” recalls Beauchamp.

The Isle of Wight trip became an annual event that the Rosslyn went on with other clubs. “We would meet in London and cycle to Portsmouth,” says Grant. “Loads of clubs would go, the boat would be filled with bikes.”

Motherhood no barrier

After Seeger’s son Tony was born, she continued to train, with him attached to her bike in a sidecar. “It was lovely. It was like a little pram; he was so comfortable,” she says. “It was like a little hammock. He wasn’t banging on the bottom; it was lined inside with nice padding.”

Beauchamp similarly took her son along with her bike. “We had a tandem with a sidecar, and we cycled all the way from Marlow, where we lived, all the way down to Bournemouth for a holiday,” she says. “He fell asleep, it was lovely. We just went everywhere on a bike.”

>>> Top five worst cycling inventions

Today, almost a century since the club first formed, its spirit is still thriving, and with no shortage of fond reminiscing. “They were wonderful, wonderful times in the Rosslyn,” says Grant. “It was lovely, the camaraderie and the memories as well.”

“You knew the Rosslyn,” says Beauchamp, “Everybody knew them.”

Race transport

In the heyday of the Rosslyn Ladies, no one had cars to take themselves to and from races. Instead, the riders had to cycle to race HQ — which was often on the other side of the country — or they had to use their initiative to save their energy for the race.

“We used to get on the back of a lorry,” explains Seeger. “I lived in Highgate [London], and quite often it was up in Yorkshire when we went to an event, or Birmingham.

>>> The top 10 road bike innovations

“They were open-backed [trucks]. It was quite nice; we’d have our lunch with us. On a good day, we’d just lie back with our capes for pillows and eat cherries, and they would drop us off as near as possible to our digs, even if it meant coming off the main road. We’d give them half a crown, two and sixpence.

“We’d do our event, 25 or 50, not too long a distance because the main event was riding home.”

The women would again use lorries on the return journey, but this time ride behind them.

“Jo, a good sprinter, would spot a lorry, hang on to it and get in the draft of it, and we’d all try to get on behind Jo.”