Iconic Places: The Cauberg, Amstel Gold Race's most famous climb

As the Classics head for the hills, for the Amstel Gold Race no ascent is more famous than the Cauberg climb

Philippe Gilbert attacks in the 2014 Amstel Gold Race

“The Cauberg is a place Dutch bike fans have made their own; like Alpe d’Huez, only playing at home.” Leo Van Vliet, former TI Raleigh pro and now the organiser of the Amstel Gold Race.

Any hill in a predominantly flat country takes on a special significance. The Netherlands is flat, but one corner of it, Limburg in the far southeast, jutting into Belgium and bordering Germany, is the exception. Its highest point, Valsenberg, is only 322 metres above sea level, but Limburg occupies a lofty place in Dutch cycling.

Limburg is where Holland’s single Classic, the Amstel Gold Race, is fought out, and its hills have been the playground for many more bike races, including some epic world titles. Inevitably though, one climb has become more famous that the rest, partly through its gradient and partly through the races it has featured in, and that climb is the Cauberg.

The Cauberg is a place every cycling fan should visit on race day at least once. It’s a smooth, steep S-bend lined at the bottom with shops and bars. It’s the only climb in cycling which actually smells of beer.

Unlike most iconic places it’s impossible to count how many times the Cauberg has featured in big bike races, because it’s been used so often, including in the Tour de France and Vuelta a España. It was climbed 26 times during the 1948 World Professional Road Race Championships alone, in a race that was contested around a tiny 10-kilometre circuit packed with 100,000 fans, and won by Belgium’s Briek Schotte.

And bike fans are part of the key to the Cauberg’s celebrity. Whatever race is contested there the fans provide a unique atmosphere. Since 2003, when Amstel Gold first finished on top of the climb, their enthusiasm has helped elevate the Cauberg to iconic status.

Street climb

The Cauberg is a street climb in the town of Valkenberg, full name Valkenberg aan de Geul after the river Geul that runs through its middle. There’s something about Valkenberg and bike racing – it has hosted four World Road Championships, every one of which was a cracker.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

The worlds have visited Holland six times, so Valkenberg is cycling city as far as the Dutch are concerned - even one of the two title races that weren‘t based there was held just down the road in Heerlen.

Limburg is perfect bike racing country. Narrow twisting roads, short steep climbs, even the infamous chicanes and speed bumps added to roads as traffic calming measures; they all combine to produce worthy winners.

Some riders hate racing here, but some hate Paris-Roubaix and it doesn’t spoil the spectacle. The roads of Limburg always produce a worthy winner.

The first was Marcel Kint, a Belgian known as the Black Eagle, an early Classics specialist who scored what is still the only consecutive triple in Flèche Wallone, but also won Paris-Roubaix and Ghent-Wevelgem.

Kint forced an early break in the 1938 Worlds, the first to be held in Valkenberg, then out-sprinted his companions on the town’s main road after 27 climbs of the Cauberg had reduced the field to a handful of finishers.

Kint’s record was good, but without the Second World War it might have been amazing. He was only 23 when he won his world title, but after taking the Belgian title in 1939 the war prevented him racing until 1943, when Kint began his run in Flèche Wallone.

The next World Championships weren’t until 1946 in Zurich, where Kint finished second after spectators held him back so a Swiss rider, Hans Knecht could win.

Part of the Cauberg’s toughness has always been the accumulated pain built by repeated ascents during a world title contest, or the 30 climbs before it in the former route of Amstel Gold Race. Also crucial was the way the Amstel Gold climbs increased in rhythm as they count down to the finish.

The route changed in 2017, with organisers vying to make the race a more open affair, moving the Cauberg back in the route and introducing a final circuit containing the climbs of the Geulhemmerberg and the Bemelerberg, before a flat finishing sprint.

But the Cauberg still remains the race's most iconic ascent.

Six climbs came ahead of it in the first 92 kilometres of the old race route, with 25 during the following 165, but the crunch came at the end with eight climbs in 42 kilometres. That’s one every 5.25km, or 7.5 minutes for a 40 kilometres per hour average.

However, the climbs averaged 1,500 metres going up, or three minutes’ racing. That makes eight sets of three-minute on, four minutes off VO2 max intervals on top of 126 miles of racing. Try it some time.

Expressed in hard numbers or graphic words the climbs beat out a cruel rhythm. The Woolfsberg, Loorberg, Gulperberg, Kruisberg, Eyerbosweg, Fromberg, and then the steepest hill of the race; the Keuteberg, 1,700 metres long with sections of 20 per cent.

They played their part when the leaders end a long gradual descent into Valkenberg at the foot of the Cauberg, and took on the final 1,500 metres of the race.

Two bridges carry the main road, the Wilhelmlaan, across the River Geul. Then folows a sharp right bend and the Cauberg begins. Gently at first, taking 400 metres to increase from two to just over six per cent, but then the real climb begins abruptly.

A steep S-bend climbing out of the town, past bars, houses and even a cemetery, it reaches nine per cent for 100 metres, then the 200 metres forming an 11 per cent crux.

Finally it eases back before the final 500 metres of dragging false flat that punishes anyone who underestimates it.

The people’s climb

But lengths and gradients aren’t really the Cauberg’s story, the atmosphere on the climb is. Dutch people love to party, and Amstel Gold on the Cauberg is an annual all-dayer. The crowds go wild and always have done. This is the people’s climb.

Way back in 1948 Briek Schotte used their reaction to keep tabs on what was happening behind him when he won his world title here.

This is what ’Iron Briek’ told Cycle Sport in 2003; “We had eight minutes’ lead, but half-way through the race I was aware of a huge reaction coming from what I guessed was the other side of the circuit.

"It was the Dutch rider Gerrit Schulte, very much the crowd’s favourite and he had attacked. From that point on I listened hard and could hear where he was from the reaction of the crowd behind me.

"Schulte was a good sprinter, who I didn’t want with me at the finish, so I decided to let him catch us just as we started the Cauberg. The crowd helped me gauge exactly where he was, and when he caught up we had just hit the climb, so I attacked flat out.

"After the effort he made to catch me, that finished Schulte as a threat and I only had the rider who had gone with me, Lazarides, to beat for the world title.”

And the crowds have only increased since the thirties. It’s reckoned that over 200,000 packed round a similar worlds circuit in 1979. The noise was deafening when two Dutchmen made the winning move, and became ear shattering when Jan Raas won for the home nation.

The fans get there early on Amstel Gold Race day, setting up camp on the pavement where they are sustained through the day by cafes, beer, hot dog and chip stalls all along the hill. The riders previously passed through Valkenberg and up the Cauberg twice before the final climb. Excitement builds all day in this open-air theatre of cycle sport so that by the end of the race there isn’t a square metre of pavement left to stand on, or a window to hang out of.

Humble beginnings

It’s all a far cry from the first Amstel Gold Race, which was a contender for the most disorganised race in history during its first few editions. Shortly before his death in 2007 the first winner, Jean Stablinski of France told us about the race in 1966.

“It wasn’t a Classic back then, just a long race, which turned out to be a very long race. The organisers measured out a route that linked all of the Amstel Brewery’s offices in Holland, or most of them, but I think they did it with a small scale map and ruler because the race was so far over the limits for a single day race, even in those days when races were longer, that they had to stick in a 40 or 50-kilometre neutralised section at the start to make it legal.

“Then there were rumours that the police were going to stop the race because of demonstrators. After that we were told that it clashed with a royal wedding in Holland, and would be cancelled. But they changed the start and the finish a few times, and eventually it was on. We didn’t complain about being messed about, because the prize money was good, more than 5,000 euros with over 1,000 to the winner, which was quite a good pay day in those days for a race that was nowhere near as hard or hilly as it is today,” he said.

The first Amstel Gold started in Breda and finished in Meersen, close to Maastricht, which is in Limburg, but it didn’t tackle many of the hills it does today. It was a flat race with a slightly hilly finish, but as the years progressed its character changed as the racing possibilities of southern Limburg, and neighbouring Belgium for a while, were discovered.

Its winners have always been quite rugged racers, some have been good sprinters too, but rarely the kind of thoroughbreds who win bunch sprints in the Tour de France. However, the winning type changed quite dramatically in 2003 when the finish shifted to the top of the Cauberg.

This was when Amstel Gold Race became spiritually as well as temporally an Ardennes Classic. It’s hills might have a different geology, but its winners have consistently been the top men in Flèche Wallone and Liège-Bastogne-Liège; whereas that was not always so before 2003.

The early hills of Amstel Gold wear down the peloton, before the attacks, tactics and leg-searing climbs of the final 50 kilometres. Since 2017 the Cauberg is climbed three times in the race with it's final appearance coming before a finishing 16km circuit, but its crowd, its smells and its gradient, all of them still enough to plant the flag of pain on anybody’s face.

Five men of the Cauberg

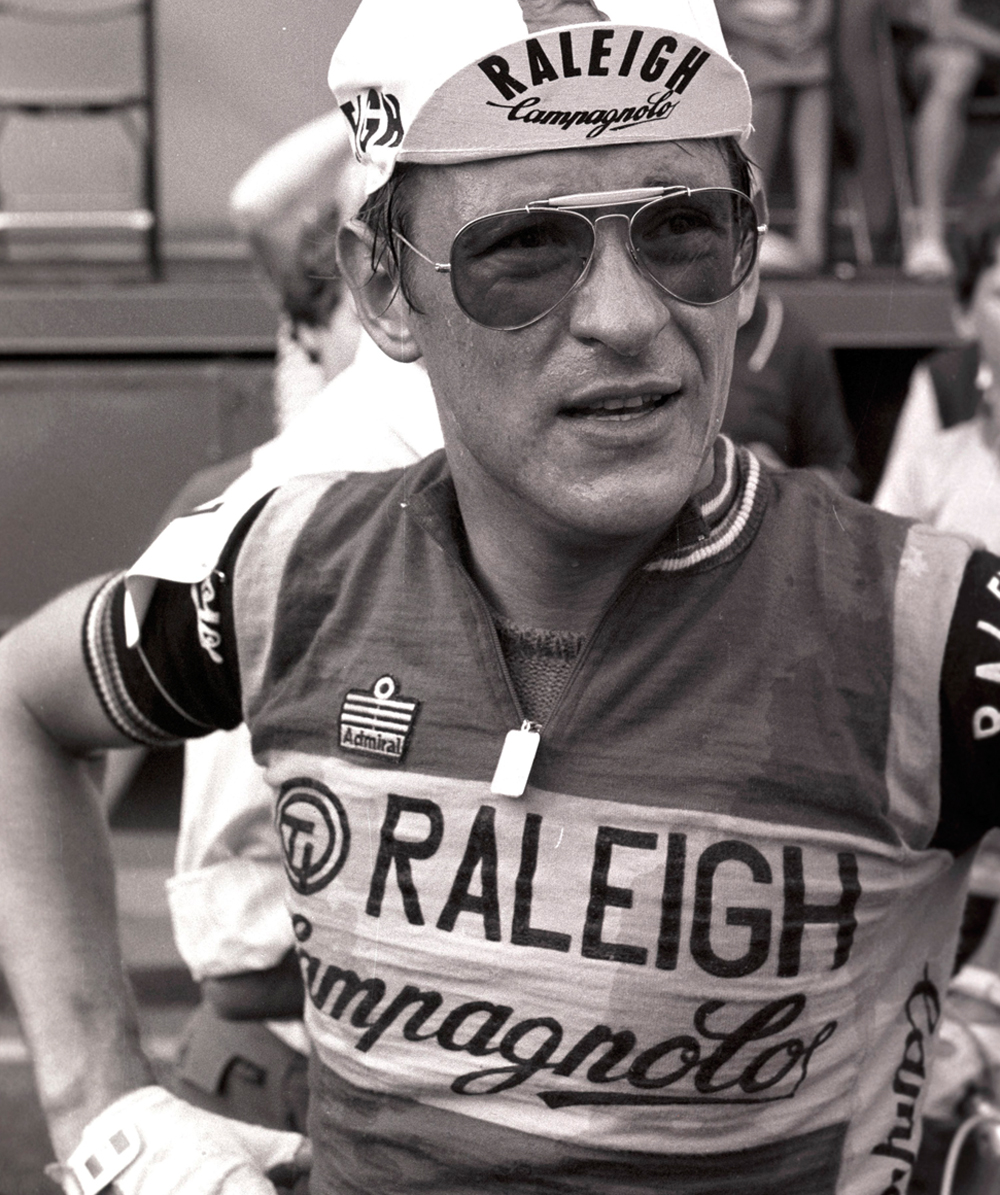

Jan Raas

He never won on the Cauberg but Jan Raas takes the title for the all-round durability he needed to set the record of Amstel Gold victories at five, four of them consecutive, and for winning his world title on a tough circuit that included this climb. Jan Raas is still the King of the Cauberg.

Raas was a tough and very clever bike racer, who had a stormy relationship with Peter Post, the manager of the legendary TI Raleigh team. They fell out over renewing his contract in 1977, but a team insider tells us that Raas hated the German rider Didi Thurau, who Post almost idolised, and that was the real reason why Raas left. Certainly Thurau had gone by the time the Dutchman returned.

As well as five Amstel Golds, Milan-San Remo and his world title, Raas won the Tour of Flanders twice, Paris-Roubaix and 10 stages of the Tour de France. His speciality was late lone attacks.

Gerrie Knetemann

Raas and Knetemann were the bespectacled Dutch twins of TI Raleigh. Knetemann was world champion in 1978, won the Amstel Gold race in 1974 and 1985 and won 10 stages of the Tour. However, Knetemann was a very different character to Raas. Where Raas was a man of few words who picked his friends carefully, Knetemann couldn‘t stop talking.

A born joker and crowd pleaser, the Amsterdam-born rider was loved by the media and fans of bike racing, and both were very shocked when he died suddenly of a heart attack while out riding with friends in 2004.

Knetemann used the Cauberg to launch his Amstel-winning move in 1974, and later he climbed it alone when riding to victory in 1985, which was a hugely significant result for the Dutchman.

In 1983 he crashed into a parked vehicle during the Dwars door Vlaanderen and almost died. He was never really the same rider after the crash, which made his second Amstel win particularly sweet.

Michael Boogerd

The Dutch called him Mr Cauberg, and Michael Boogerd has crossed the top of the climb more times in the first three of Amstel Gold Race than any other rider in history. Just the sight of the Cauberg provoked some kind of Pavlovian reaction that made Boogerd attack. After winning Amstel Gold Race in 1999, Boogerd took three second places and two thirds. Incredibly, between 1998 and 2007, the year he retired, he finished in the top 10 of the race every year.

Fränk Schleck

The Luxembourg rider used the steeper Keuterberg to launch his winning solo attack in the 2006 Amstel Gold Race, and it was one of the great victories in the young Classics specialist’s history. Schleck rode magnificently to hold off the chasers with the help Karsten Kroon from his CSC team, who was able to interfere with the chase behind. His knock-kneed, fast cadence ascent of the Cauberg was one of the highlights of Schleck’s career.

Malcolm Elliott

One of the few British riders to stand on the podium of a Classic is Sheffield’s Malcolm Elliott, and he achieved the distinction with third place in the 1987 Amstel Gold Race. What is more, where the other British racers achieved their positions as part of well funded and well established pro teams, Elliott was part of a largely British-staffed ANC team who were dipping their toes in top level racing.

In the closing stages Elliott found himself with three Dutchmen, Steven Rooks, Teun Van Vliet and Joop Zoetemelk, plus Bruno Cornillet from France. He survived a blinding attack by Rooks on the Cauberg, but then the Dutchmen attacked Elliott in turn, fearing his sprint, and when the great but ageing Zoetmelk ‘dieseled’ off the front and Elliott couldn’t chase, the others let him go, preferring that a local rider one than an upstart from a small British team.

The original version of this article first appeared in Cycle Sport’s Iconic Places series in June 2010

Chris has written thousands of articles for magazines, newspapers and websites throughout the world. He’s written 25 books about all aspects of cycling in multiple editions and translations into at least 25

different languages. He’s currently building his own publishing business with Cycling Legends Books, Cycling Legends Events, cyclinglegends.co.uk, and the Cycling Legends Podcast