Eddy Merckx: the man behind the legend

Winner of over 500 races, era-defining rider, son of a grocer and a grandfather just turned 71. Who is the real Eddy Merckx?

Photo: Chris Catchpole

Sports fans always like to fire up the old debate over who is the greatest in a sport’s history. Is Pele, Maradona, Ronaldo, or Bobby Moore the greatest ever footballer? In tennis is it Roger Federer, Pete Sampras, John McEnroe or Steffi Graf?

When it comes to cycling the debate never gets very far. We know the answer. Eddy Merckx is the greatest cyclist of all time.

During his career from 1965 to 1978, the Belgian won 525 races. He is still the joint record holder for the number of Tour de France overall victories (five). He has undisputedly won the most Tour de France stages (34), the most Grand Tours (11) and the most Grand Tour stages (64).

He has won the most Monuments (19) including seven victories at Milan-San Remo. He broke the Hour Record. He was the first rider to achieve the Triple Crown of Cycling — victory in the Tour, Giro d'Italia and World Championships in one season — and only one other rider, Stephen Roche, has done so since.

In 1971 Merckx won 45 per cent of the races he started. Come up against Merckx during that season and your chances of victory as a rival rider were as good as halved before you’d even begun.

There is just so much. There’s a bronze and stone monument dedicated to Merckx at the top of

the Côte de Stockeu, a steep climb used in Liège-Bastogne-Liège, which lists his achievements. It simply ends with the word ‘etc’. There isn’t even space to mention the fact that he won Paris-Roubaix and Paris-Nice three times each.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

But reducing Eddy Merckx to mere statistics is missing the wood for the trees, like talking about Van Gogh’s ‘Sunflowers’ as a collection of coloured pixels or one of Mozart’s symphonies as a big bunch of notes.

In his native Belgium, Eddy Merckx is a combination of David Beckham, Paul McCartney and Winston Churchill. Eddy Merckx is a sporting god, a style icon, and a national hero.

In a 2005 TV poll he was voted the third greatest Belgian of all time (and Merckx is the only person in the top 10 who is still alive). In 2003 a station on the Brussels underground was named after him and his Hour Record bike was encased in glass within it.

Did you know?

Eddy Merckx once raced at Eastway

It was June 11, 1977, the Glenryk Cup, and Merckx turned up with the likes of Raymond Poulidor and Luis Ocaña. Sid Barras won the sprint.

Eddy Merckx never won Paris-Tours

The end-of-season Classic was the one race to evade him. His best place was sixth in 1973.

Eddy Merckx could have been even better

Merckx remarked that he was never the same again after a serious crash on the track in September 1969, which killed his derny pacer Fernand Wambst. The injuries led to him continually adjust his bike for the rest of his career.

Meeting the master

We’re in Belgium to interview Merckx at the Eddy Merckx Cycles factory on an industrial estate off the Brussels ring road.

Just being here helps you understand how big a name he is. He has been interviewed so many times that, if you’re not careful, he answers your question with a stock answer that he’s given dozens of times before without even realising it.

>>> Brussels exhibition celebrates the life and career of Eddy Merckx (video)

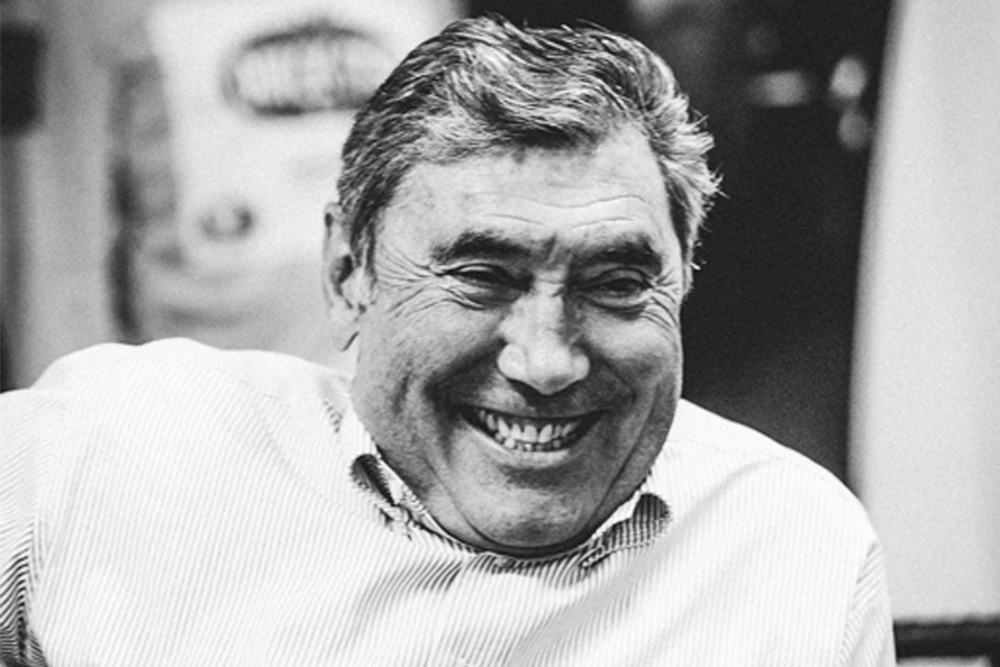

In a country where cycling amounts to a national sport, Merckx is public property. Everybody here knows the story of the grocer’s son from the Brussels suburbs whose first victory came at the age of 16 and who turned pro five years later. Everybody recognises that trademark smirk, those long cheeks and those dark eyebrows. And everybody wants a piece of him.

“I don’t go to bike races that much anymore,” Merckx tells Cycling Weekly. “I’m just fed up of having my picture taken and signing autographs. That’s not my thing any more.”

The reality is that the Eddy Merckx of 2016 is not the Eddy Merckx of the 1970s. He’s now 71 years old. Eddy Merckx is an old man. Wrinkles and creases now frame his famous features. Not that it matters to Belgians. Or to Merckx.

“It’s a catastrophe!” he jokes as his recognisable smile creeps across his chin. In fact, quite often over the course of our interview Merckx makes a deep rumbling noise when he doesn’t quite agree with a line of questioning: a roar that says, ‘Now hang on just a minute.’ We ask him whether he feels his age.

“Bwaar,” he bellows, “70 is 70. I like to say that when you start with 100cm and you cut off 70cm, you’ve still got plenty left, eh? What’s important is good health, and making the most of it.”

Maybe he doesn’t like to be reminded of it, but Merckx has aged. In 2014 he was out cycling when a car drove into his back wheel, hospitalising him with a broken shoulder, a damaged knee and torn hip ligaments. Earlier that year he underwent a heart operation to treat his cardiac arrhythmia, a little over 12 months after being fitted with a pacemaker. He’s been told he shouldn’t take his heart rate above 145bpm.

Yet Eddy Merckx is a happy, down to earth man. He’s never been one to embrace celebrity or the high life, but these days he likes to keep out of the public eye more than ever.

“I don’t have too much on these days,” he says. “I go cycling, I organise the tours of Oman and Qatar, I go to the football, I go to watch the hockey, I watch TV.”

>>> How Eddy Merckx put the Middle East on the cycling map

We get the feeling that these days Merckx just wants to be normal. In an attempt to get him talking, we ask him about his reported interest in surrealist art.

“Yeah, but no,” he says. “I had a Dali drawing once but I don’t know all about it that much.”

Being Eddy Merckx, the greatest living Belgian and the best bike racer of all time, is quite enough for one man’s plate without having to be a surrealist art connoisseur as well.

He says he likes to stay at home of an evening and watch TV quiz shows with his wife of 48 years, Claudine. But as he says it, he looks at us with the slightest bit of mischief, as if he knows that the Eddy Merckx everybody knows shouldn’t be slumping on the sofa in front of the box.

He should be out there gobbling up life with the same appetite with which he gobbled up races. But don’t mention the R word. Eddy Merckx is emphatically not retired.

“No, no, no,” he says. “I keep myself busy. I don’t want to spend the whole day on the sofa."

Getting on

Being here, it’s very difficult to reconcile this chatty old man with the Eddy Merckx of countless biographies and photography collections and the Eddy Merckx who sits in the background of cycling as a yardstick for achievement even today.

To a certain extent, this old Merckx has had enough of that old Merckx. He’s still got the slim, cyclist’s legs — 13 years as a professional leave their mark — but he admits that he doesn’t have any photos, jerseys or memorabilia from his riding career around his house.

All he has on display is one gold medal from the 1967 World Championships and a photograph of his son, former pro rider Axel, with his bronze medal from the 2000 Olympics — the one achievement that eluded Merckx Senior.

>>> Icons of cycling: The Rainbow Jersey

Much of the rest has gone into boxes in the loft or been given away to sponsors. Merckx’s generosity, particularly when it came to old jerseys and bikes, is a common theme when talking to those around him.

He was also burgled in the 1970s and lost much of his valuable memorabilia in the raid. We later learn that Merckx is in the process of buying back some of the old bikes he lost, though he doesn’t like to wallow in the past.

“I’m not too nostalgic,” he says. “I remember what it was like to be 15 and wanting to become a pro cyclist. It was a really nice time in my life. But it’s gone.”

There is one reminder he’s very happy to have around: his grandson, Luca. Eddy Merckx is a doting, generous grandfather who loves to spend time with his grandchildren, which he explains has helped to make up for the time lost with his own children while he was busy riding his bike.

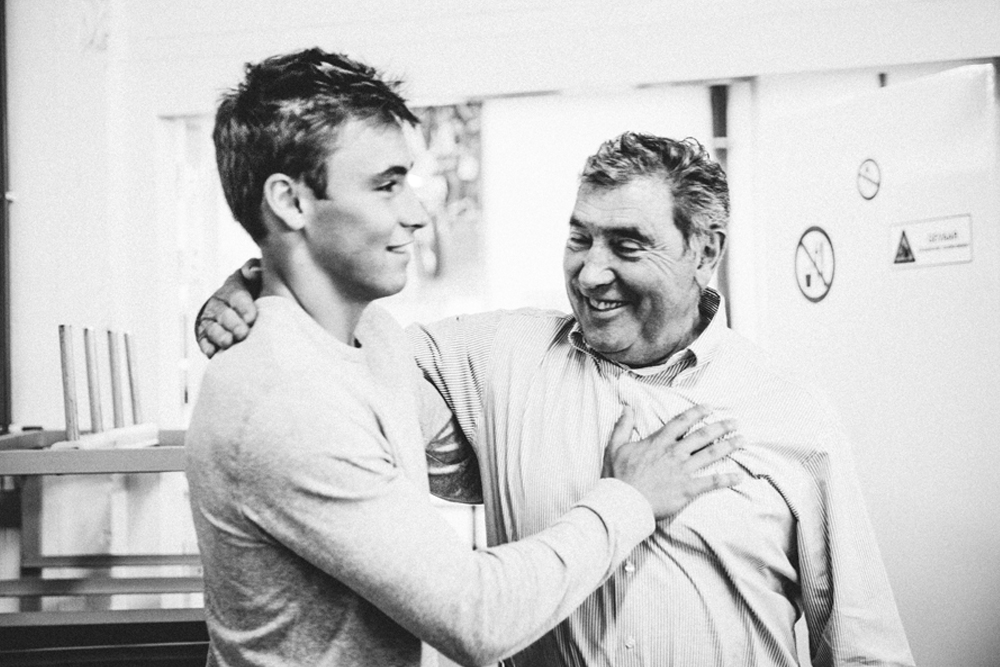

And Luca, who is in the middle of a marketing internship at Eddy Merckx Cycles and sits in on our interview to help translate the odd word from French, is an uncanny visual reminder of his grandfather’s heyday.

>>> Top seven father and son combinations in cycling

He looks like the boy at school who was annoyingly good at everything: the straight-A student who was funny, made the first team, and got the girls.

You can feel a sense of what it must have been like to line up on the start against Eddy. As was often said at the time, it must have felt like he’d beaten you before you’d even begun.

Luca is an echo of Merckx, two generations down the line, except that Luca plays hockey. Unsurprisingly, we’re told he’s very good.

Merckx, Froome and the French souvenir

Despite Merckx’s staggeringly prolific career, the public didn’t always warm to him for it. There are interesting parallels with events 40 years later, when Chris Froome and Team Sky were on the receiving end of physical and verbal abuse during the 2015 Tour just as Merckx was in 1975.

The man himself has come to terms with the response, even if deep down he still can’t understand it.

>>> Merckx: Froome will win the Tour again as he has no real rivals

“It’s the… it’s a French souvenir!” Merckx laughs. “There are idiots everywhere, but the majority understand sport.

“I can imagine what he [Froome] was feeling. You don’t forget it, but at the same time, the important thing is who wins.”

Will to win

Considering Merckx’s reputation as a rider, is it not slightly ironic that he has let so much of his memorabilia disappear?

To us, Eddy Merckx was a man who was relentless in his quest for victory; a rider nicknamed ‘the Cannibal’ by the daughter of one of his team-mates because he devoured everything and everyone around him. You don’t get a name like that for being generous.

“I’ve had it since birth,” he explains. “When I was little I played football and I wanted to win. I played basketball and I wanted to win. I played cards… and I wanted to win.

“I don’t know how to lose,” he adds. “It’s not that I fear losing, I’m just a bad loser.”

It often came across as aloofness or insouciance but the hallmark of Merckx’s dominant riding style was actually a product of anxiety as much as it was greed.

Even when commanding an enormous advantage over his rivals Merckx often worried that it wouldn’t be enough.

There was the 1969 Tour of Flanders where he attacked brazenly with almost 45 miles to go, leading his manager Guillaume Driessens to drive up alongside him in his Peugeot 404

team car in a mad panic and shout at him to stop. He didn’t, and he won.

The report in this magazine at the time called it “another shattering victory which had reduced all but a handful of his contemporaries to the level of tourists.

“The extraordinary Merckx was so strong,” it added, “that he was able to ride the last 70km on his own, in glacial rain and against the wind.”

How they used to train: Eddy Merckx's chain gang

He might have been the greatest male road racer ever, but Eddy Merckx also built one of the best teams

Eddy Merckx in 10 questions

To mark the great man's birthday earlier week, we want to see how well you know The Cannibal in this

It was a style of racing that came to be dubbed la course en tête — a triple-entendre that can be translated as ‘racing from the front,’ ‘racing above all else’ and ‘racing stuck on your mind’.

The most clear example of this is his most famous day on a bike, the 17th stage of the 1969 Tour de France. With over eight minutes’ overall advantage over his nearest rival, Merckx attacked alone down the Col du Tourmalet, soloed the Col d’Aubisque and won by almost eight minutes at the finish in Mourenx. Once again it delighted the Cycling headline writers.

“All the way, every way, it’s Merckx,” they said.

“Master in every sphere… Eddy Merckx, the complete champion, has the Tour de France in his pocket,” the report added, re-emphasising that Merckx “made his rivals look simply ridiculous”.

It was tantamount to pulling his rivals’ trousers down around their legs, although it was probably not always Merckx’s intention to embarrass them in such a way.

>>> Icons of cycling: Plum bike shop, Ghent

Eddy Merckx is his father’s son. Today he suggests that his attitude and work ethic were inherited from his dad, a grocer and shopkeeper in Woluwe-Saint-Pierre on the edge of Brussels.

“The important thing is to remain yourself, and never to believe that you’ve made it, you always have to work,” he says. “I believe that the most important thing is to keep your two feet on the ground and never believe that you’re the best and that there’s nothing left for you to do.

“You have to ask questions of yourself every year, at the start of each season. And I found at the start of each year that there was a certain anxiety I had, there would be other riders who would be good or new young riders entering the ranks… It’s not like someone getting a diploma at university to be a pharmacist all his life [Merckx’s brother, Michel, is a pharmacist]. If you’re a cyclist, every year you start anew, and you have to get your diploma again at the end of every year.”

In the end, though, all that course en tête just wore him out. Riding from 1965 to 1978, Merckx’s 13-year career was relatively short considering that two of his contemporaries, Raymond Poulidor and Joop Zoetemelk, enjoyed careers of 17 and 18 years respectively.

>>> Pro cycling face mash-ups: can you tell who’s who?

He says now that he knew the writing was on the wall when, in the 1975 Tour, he was punched by a spectator on the Puy-de-Dôme and later fell in the Alps, breaking his jaw. He continued to second place (and the financial rewards), still attacking his rivals, but was never the same again.

“The only regret was that I finished the 1975 Tour,” he says. “Afterwards, all my problems stemmed from that.”

There’s a quote attributed to Merckx from 1972 that does a very good job of summing up his attitude to cycle racing. He had just ridden over the Col d’Izoard and down into Briançon, winning a classic stage that echoed the legendary rides of Fausto Coppi and Louison Bobet, whose memorials stood on the upper slopes of the climb’s famous casse déserte.

It was a ride which cemented his place in the pantheon of greats, in particular for the nostalgia-fuelled French press and public.

“People talked to me about the casse déserte and Fausto Coppi’s monument fixed to a rock,” Merckx said at the time. “I didn’t see any of that; I’m sorry but I was too busy.”

It’s one quote that captures the hype and expectation surrounding Merckx, his general lack of interest in the romance of the sport and his total devotion to winning.

It also points to his human side. He says sorry, as if he understood that he wasn’t always the champion that people want him to be. Because the public, especially outside Belgium, never loved Merckx like they loved Poulidor, the eternal second, or like they today love Peter Sagan, the cheeky, charismatic Slovak with a reputation for coming second.

Merckx was respected, but he was too good, too dominant, and too flawless to be loved. He might have been the man who didn’t know how to lose, but ultimately Merckx could never win the public’s heart.

Carefree charisma

Perhaps that has changed. These days Eddy Merckx is curating his Sagan-esque cheeky side. He’s not pulling wheelies and dressing up in fur coats, but he has the carefree attitude of a man who commands the same aura he did when he was racing and knows he doesn’t need to work for a living any more.

At times it sounds like his main preoccupation is stopping himself from getting bored.

He was tempted over to London for a recent cycling exhibition when organisers took his bucket list and prepared a weekend of activities to keep him occupied.

Having been picked up from the train station in a Maserati sports car, he went to a track day, watched Chelsea play Norwich City from the directors’ box at Stamford Bridge, went down to meet the players, and then went wine tasting in the capital.

But then boredom must be a problem for someone of Merckx’s ilk. If boredom isn’t the right word, then a sense that whatever he achieved from 32, his age when he retired in the spring of 1978, nothing would ever equal or exceed his achievements in cycling. Talk about a midlife crisis.

It’s no good Merckx waiting for a successor either. There has never been a rider like him before or since, and nor will there be. Cycling has changed. John Degenkolb will never win the Tour and Chris Froome isn’t going to win Paris-Roubaix any time soon.

Eddy Merckx is, and will remain, the best rider of all time.

Today Merckx is involved with his bike business once again (see below) after it was taken over by new majority shareholders Diepensteyn, a firm specialising in Belgian heritage brands like Palm beer and a range of castles and stately homes.

But his role is limited to an ambassador and creative adviser and, like everything else, it cannot fill the space left by bike racing.

“It’s a satisfaction when you see that you’ve made something of a good enough quality that the pros are happy to ride it,” Merckx says. “The employees were happy when an Eddy Merckx bike won something. For me it gave me pleasure too, but it’s not the same thing as winning yourself. But it’s nice.”

Yet just as Eddy Merckx the bike racer was never comfortable resting on his laurels, Eddy Merckx the 71-year-old isn’t entirely comfortable in retirement either.

He’s still out there, looking to the next task confronting him and trying to win at it. In his case that challenge might just be living the life of a normal man at last.

“Age doesn’t change anything,” he says. “It happens to everyone, doesn’t it? You have to make the most of life, make the most of being a grandparent, and be grateful that you’re still able to ride a bike.”

Back in the bike business

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_lBD39aNQBk&feature=youtu.be

Eddy Merckx is a perfectionist, in particular when it comes to his bikes. After his infamous crash in 1969 on an outdoor track in Blois, and subsequent injuries, he became an obsessive tinkerer, forever adjusting his measurements. In the film A Sunday in Hell, Merckx stops several times to adjust his saddle height mid-race.

Merckx started his bicycle company in 1980 with help from Ugo De Rosa, the legendary Italian frame-builder who crafted many of Merckx’s bikes (to his very exacting requirements) during his post-injury career.

Eddy Merckx Cycles provided bikes for teams such as 7-Eleven, Motorola and Quick Step but after issues with tax, financial mismanagement and a falling out with former majority shareholders, Dutch footwear giant Brantano, Merckx sold up and took a step back. Now though, with new owners, he’s back on board.

As a further measure of the weight of the Merckx name, the current boss, Dutchman Rob Beset, recalls his cycling-mad father crying when he told him over the phone that his son was going to work for Eddy Merckx.

“It sounds a bit emotional, but he’s very warm to work with,” says Beset. “With him it’s very clear, he has his opinions and statements and is open to discuss them.”

The company has now turned annual losses into profit, and recently poached chief development officer Rolf Singenberger from BMC to work principally on its new EMX-525 model. This year the company also produced the EDDY70, a limited edition steel-framed bike with special edition Campagnolo Super Record.

>>> Icons of cycling: Campagnolo Super Record derailleur

Johan Vranckx, a frame-builder at the company for 35 years, made just 70 by hand. Number one went to Eddy himself and the remaining 69 sold for €14,000 each.

Eddy Merckx rides an electric bike?

Just before interviewing Eddy Merckx we’re told by one of the company bosses that he has one of their prototype electric bikes. Somewhat sheepishly we ask him, “Eddy, we hear that you ride

an electric…”

“Well, I have an electric bike, but more often I go out on a normal bike,” he interjects. “When I go out with my mates I go out on a normal bike.”

Merckx now rides purely for pleasure, often out with his old team-mates and contemporaries Jos Spruyt, Roger Rosiers, Jos De Schoenmaeker and Willy Vekemans.

No longer does he lead them on epic winter training runs from one end of Belgium to the other and back. These days it’s a 75km run to the cafe.

“We stop the ride where there’s a cafe where they have a big Berkel, a machine to cut San Daniele ham from Italy, and we stop for some ham and a beer or a glass of wine, that’s what’s important these days. And now, winter is for resting.

“Cycling was always about the pleasure of riding a bike,” he adds. “And now it’s the same, the pleasure of riding without the constraint of having to win. Although, I still look out for any idiots who might crash in front of me.”

Richard Abraham is an award-winning writer, based in New Zealand. He has reported from major sporting events including the Tour de France and Olympic Games, and is also a part-time travel guide who has delivered luxury cycle tours and events across Europe. In 2019 he was awarded Writer of the Year at the PPA Awards.